China’s frontiers: Is there anything left to explore?

— June 11, 2014

If it’s too easy, then it’s not real exploration.

So says Wong How Man, a Hong Konger who in 1974 began leading expeditions into what was then one of the world’s most isolated countries — China.

“It was a time when China had very few friends, so we decided to step in and help with what we could put together; funding and expertise,” says Wong, founder of the China Exploration & Research Society.

In those early days China was only just opening up.

It was the tail end of the Cultural Revolution and there were a lot of restrictions.

Bureaucracy and disappointment were the order of the day.

Wong doesn’t like to recount the red tape he faced because “it’s like living through the pain.”

A number of times when he returned to Los Angeles, where he was living at the time, he considered switching his expeditions to another part of the world.

But China always drew him back.

Remote regions open up

Today it’s a very different place.

Today it’s a very different place.

Rapid development hasn’t just boosted the economy — it’s opened up vast swathes of the country.

In 1985, when Wong led an expedition to find the source of the Yangtze River, he says he and his team traveled for nine days on horseback.

They faced not only the challenge of high altitude, but snow, rain and hail.

He returned 10 years later to find the same journey took just five days.

Another decade saw times reduced even further.

“When I did it in 2005, it took just three days because the road was much closer. Now we could probably drive all the way to the source,” says Wong, who began leading expeditions for National Geographic before setting up CERS.

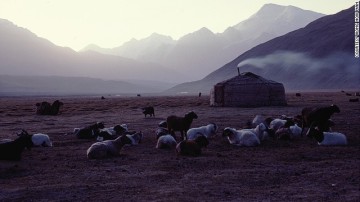

Expeditions into western China once involved huge amounts of off-roading, but today large mining companies are on the ground and the region is crisscrossed with roads.

“Now if we get stuck, we ask for help from the miners,” says Wong.

Though easy access is opening up once very remote regions, the traditional way of life is disappearing.

In 1985 Wong says he discovered a small community that trained otters to help them fish.

Twenty years later just one family still used this technique.

“Before there was this wide open field to explore,” says the 65-year-old former journalist.

“When you have roads going in left and right, if you have to look really hard to explore, then maybe it’s not where I want to be.”

The next frontier

Today Wong has to look harder to find truly out of the way places he deems worthy of exploration.

Today Wong has to look harder to find truly out of the way places he deems worthy of exploration.

He says the best remaining sites are on China’s frontiers.

China shares land borders with 14 countries — Mongolia, Russia, North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, India, Bhutan, Nepal, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan.

The often complex cultural and historical backgrounds of frontiers can make them especially interesting, but timing is everything when it comes to the exploring border regions.

As its relationships with its neighbors are sometimes volatile, countries fall in and out of favor.

“You always have to look at timing. What wasn’t possible suddenly may become possible,” says Wong.

During a visit two years ago to China’s border with Vietnam, Wong said political unrest made exploration problematic.

On the Indian border, it’s currently a different story.

China and India’s political and trade ties are better than they’ve been for many years, opening it up to exploration.

Wong’s top frontier pick is China’s northeastern border with Russia.

While the Harbin Ice Festival might draw the crowds, he says this is the place to be in winter.

Here, the Amur River freezes so solidly that it’s possible to drive over it in a four-wheel drive vehicle.

Wong went there recently to catch up with some reindeer herder friends.

“You can drive almost to the source of the Amur River, the 10th longest river in the world, and see the border troops talking to each other, people ice fishing and crossing the river even through they’re not supposed to,” says Wong.

The Chinese border with Laos, near the Golden Triangle, is another region ripe for exploration, particularly for those interested in hill tribes.

“It’s fascinating to look at the dynamics between people at borders,” says Wong.

“A lot of the time the locals are closer to the people across the border than they are to their respective governments, which are far away.”

Wong says the border between China’s southwestern Yunnan province and Myanmar is also ripe for exploration, as it is free from the political complications of more sensitive areas close to Tibet or Vietnam.

Still, Wong can’t resist a challenge.

He recently set off on a month-long expedition to western Tibet — a trip made easier by a new road, but complicated by red tape.

New visa regulations made it impossible for non-Chinese members of the team to join.

As always, he is prepared for further trouble and has several backup plans up his sleeve.

“Exploration has to involve some logistics, some difficulty. If you’re like a sprint runner, ‘Oh, I got there first and I’m home already and on the computer sharing it on Facebook,’ then I don’t call it exploration,” says Wong.

Original Link: CNN

Leave a reply