New symbol of Islamic art

— December 1, 2015Forget the murals of camels in the desert and finely woven tapestries – the recently opened Yinchuan Museum of Contemporary Art is bringing a starkly modern vision to the art of the Silk Road

![]()

LET ME PAINT you a picture. An expanse of reeds rustle amid wetlands, with sunflowers beaming towards an uninterrupted blue sky. The Yellow River is rushing in the distance. Twenty-five kilometres outside Yinchuan, the capital of the northwestern Chinese province of Ningxia, it’s a classic rural scene of the ancient Silk Road – except for one incongruous blip interrupting the hori- zon: a thoroughly avant-garde building, resembling twisting white ribbons, rising from the plains.

That building is the new Yinchuan Museum of Contemporary Art, or the MOCA Yinchuan. Opened in August, this 15,000-square-metre structure sits in the middle of an organic plantation on the banks of the Yellow River and is the latest in the boom of private museums that have opened across China in the past decade.

‘I’d only been here seven days when they asked me to find a definition for the museum,’ recalls the museum’s artistic director, Hsieh Suchen, who packed in her job as director of the Today Art Museum in Beijing to take on the project. ‘I didn’t want to do the same as all the other museums.’

In developing its ‘definition’, the mu- seum looked to the city’s people and his- tory. In Yinchuan, which is an hour’s flight from Xi’an, more than a quarter of the local population is Muslim. Located along the Silk Road, the city drew traders from the Middle East over centuries, many of whom settled and married local women.

This cultural legacy led Hsieh to MOCA Yinchuan’s vision: a museum dedicated to Chinese and Islamic contemporary art. And the pieces it shows are certainly a far cry from the murals, tapestries and grottoes many would associate with Islamic art along the Silk Road. Instead the museum has a thoroughly modern proposition, exploring the intersection of cultures in the modern world, with provocative works bringing to the fore numerous human rights issues – includ- ing women’s rights, children’s rights and land ownership – and forcing visitors to confront these problems.

This cultural legacy led Hsieh to MOCA Yinchuan’s vision: a museum dedicated to Chinese and Islamic contemporary art. And the pieces it shows are certainly a far cry from the murals, tapestries and grottoes many would associate with Islamic art along the Silk Road. Instead the museum has a thoroughly modern proposition, exploring the intersection of cultures in the modern world, with provocative works bringing to the fore numerous human rights issues – includ- ing women’s rights, children’s rights and land ownership – and forcing visitors to confront these problems.

‘People close their eyes and think the world is beautiful, but in some corners these problems always exist,’ Hsieh says.

The building itself sets the contem- porary tone. Conceived by Beijing-based firm We Architect Anonymous, it is designed in response to the natural envi- ronment – the wetlands, the river and the desert just beyond.

‘The Yellow River passes by the site. As the water flowed by, it shifted the sands of the riverbed. Gradually this build-up of sediment created bumps – this is what inspired our design,’ says Zhang Di, a prin- cipal partner at WAA, of the fluid lines on the building’s interior and exterior.

And then, of course, there’s the art. Art critic and art historian Lu Peng, who serves as the director of MOCA Chengdu, has been involved with the project from the start and conceived the overall theme for the six opening exhibitions, collec- tively called ‘Dimensions of Civilization’, which launched in August.

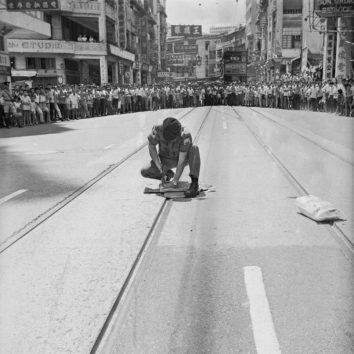

The exhibitions encompass works by big names in Islamic art as well as emerg- ing artists. Standout pieces include the video installation Witness from Baghdad by Iraqi artist Halim Al Karim, a response to the first Gulf War, and Elektra KB’s provocative The Journey, a canvas depict- ing women in frilly short skirts and head coverings holding rifles.

‘I wanted to explore the relationship between different civilisations through different themes – Chinese and foreign, ancient and modern,’ says Lu. ‘Yinchuan has many Hui people, and the city’s history and culture provide a special backdrop for the museum.’ The Chinese Hui Muslim minority is descended from Arabic and Persian merchants who came to China during the seventh century, and the vast majority live in the Ningxia. Many of the young museum ambassadors who welcome visitors are Hui.

The art isn’t restricted to works hang- ing on the walls; there are several huge sculptures outside the building, irrever- ent art works that set out to shock. Chief among them are three horse sculptures by Beijing artist Liu Di, one of which is on its back, kicking up its legs.

This is only the first phase for MOCA Yinchuan. The museum itself is part of a larger complex, funded and conceived by Liu Wenjin, an industrialist. Next summer will see the opening of an artists’ village not far from the museum. Currently under construction, the red-brick village will feature 23 artist studios, each one a stand-alone home with a kitchen, a bathroom and several bedrooms so visiting artists can bring their families.

‘I want to invite artists from all over the world, not just Chinese artists, because we must learn something from the outside,’ says Hsieh. ‘I hope we will see more Muslim artists. And there will be a huge gallery where they can exhibit their work.’

Also happening next summer will be a three-day Simple Life Festival, an event that began in Taiwan as a music festival but has evolved to promote organic and sustainable living. Meanwhile, plans are underway for a hotel that will make use of water from two nearby lakes and, like Sim- ple Life, embrace a healthy lifestyle and sustainable living. These projects reflect MOCA Yinchuan’s goal of using the area’s natural assets and rich cultural legacy to make a positive impact on visitors.

Not only does MOCA see its art shed- ding light on modern Islamic culture, but collaborations between artists of different backgrounds will also act as a bridge between cultures. For many people, Hsieh says, Muslims are little understood beyond their practice of not eating pork and daily prayers, ‘but that’s such a small part of the picture. Little by little I hope that the museum will help to integrate cultures – it’s a kind of soft power’.

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/374-SilkroadMOCA-Yinchuan.pdf]