Paralysed scientist healed himself with alternative medicine

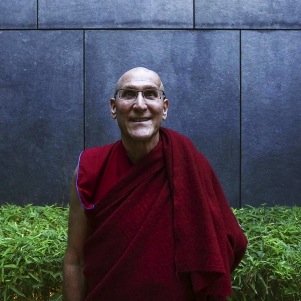

— November 9, 2015Neurologist Charles Krebs, left paralysed after a diving accident, got back on his feet thanks to kinesiology, a mix of Chinese acupressure and Western medicine. He’s since spent his life exploring the science behind it and perfecting the therapy.

Charles Krebs didn’t set out to be a star in the world of alternative medicine. He did a degree in physiology at Boston University, then a PhD in evolutionary biology and paleontology and followed that up with a degree in marine science. After teaching at St Mary’s College in Maryland for years he moved to Australia in 1983 to work as a marine research scientist. So far so very mainstream scientific – until a near fatal scuba diving accident left him paralysed and set him on a journey to heal himself through alternative medicine.

The accident happened soon after he arrived in Australia. Aged 32, he was on a dive trip with friends at Wilsons Promontory in Victoria, a remote spot just off the coast. All were well experienced and they had been preparing for days for the final dive to 60 metres by gradually diving deeper each day and taking the other necessary precautions. The dive itself went fine. Back on the boat, his wetsuit off, Krebs noticed a medical dive book. He flicked through the pages and began reading the section on the “bends”, also known as decompression sickness.

There are two types of “bends” – the first is when nitrogen forms in your joints, it’s very painful but goes away in a few days. The second is when nitrogen forms in your spinal cord, it swells up and blocks the blood flow. According to the book, there are two things that confirm type two bends: you get locomotive incoordination, in other words you stagger; and you can’t pee.

“I thought, ‘Oh, this is very interesting’. Then I had to take a pee so I walked to the head of the boat and my arms were shaking and I thought, ‘What’s this?’ I got to the head of the boat and I couldn’t pee,” says Krebs.

He had type two bends. Through a series of fortunate coincidences help rallied around fast – experts in decompression sickness were not far away, a special saturation chamber was located – but despite the valiant attempts of his wife and others to get help he spent 5½ hours waiting for a helicopter as paralysis spread from his feet to his neck.

“Because I’m a neurologist and taught anatomy and physiology, I know the whole nervous system, I can visualise it in my head. And I was just seeing that L4, L5 – I was just watching myself become progressively paralysed, but I had this view that I would get decompressed and everything would be OK,” says Krebs.

It wasn’t that simple. By the time the helicopter arrived he was a C6 quadriplegic. A standard 24-hour decompression didn’t help, nor did further time in the chamber.

A decompression specialist suggested an untested treatment that involved raising the level of oxygen level in body by 40 minutes out of every hour breathing 60 per cent oxygen. It was like breathing liquid fire, but by the third day of treatment he had control back of his arms and hands. When he left the decompression chamber 10 days later he was a T9 paraplegic and in a wheelchair.

In hospital and then rehab, he watched other patients sitting around all wondering the same thing – why me? Determined to walk again, he drew on his nine years of teaching anatomy and physiology, his years of martial arts training which had taught him to move chi around the body and a rather useful holographic memory – “I see things in 3D in my head”. So while most of the others in rehab were watching TV, he was turned inward.

“I would pick a muscle that doesn’t work and would run chi down that nerve pathway to that muscle hour after hour. After days or a week, suddenly I would contact the muscle. Then I asked the physiotherapist what exercise I needed to activate that muscle and I would sit there and visualise myself doing that exercise as I ran chi. Pretty soon it moved a little,” says Krebs.

Once he could get his foot off the floor, he began trying to lift a 500 gram weight, then 1kg until he built up his strength. Nine months after he went into rehab a paraplegic and was told he’d never walk again, he walked out with the aid of crutches. He was put on sickness benefits for a year and spent the time doing some serious meditation, went to ashrams and practised moving chi.

His friends knew he was open to alternative treatments – some worked, others didn’t – so when one spotted an ad for kinesiology he made Krebs an appointment. He hobbled into the session arching his hips and dragging his feet, leaning heavily on his cane.

“I lay down and my arm was moved up and down and he touched acupoints. I was thinking this is one of the weirdest things ever, but the guy was a medical doctor so I thought, I’ll go with it. Ninety minutes later I walked out carrying my cane – that was a profound reorganisation of my neurology in an hour and a half,” says Krebs.

Three days later he began his first kinesiology class. Kinesiology is a non-invasive energetic healing science. It has its origins in the 1960s when chiropractor Dr George Goodheart discovered that muscle testing could be used to gather information about the body. This system was called “Applied Kinesiology” and quickly became popular among chiropractors.

Kinesiology integrates traditional Chinese medicine techniques and Western muscle monitoring to balance the body. Practitioners learn how to access the movement of energy through the body. By learning muscle monitoring techniques they are able to detect where energy is blocked or stressed.

Helen Griffiths is one of eight practitioners at Kinesiology Asia. Founded in 2006 by Brett Scott it is Hong Kong’s first centre dedicated to the practice. She came to kinesiology to work through some difficulties and got such positive results from it she decided to study it.

“We use muscle response to connect to subconscious stresses in the system. Through the muscles, which are connected to the brain through the central nervous system, we are able to pick up on any stresses that might be there,” says Griffiths.

Kinesiology is very good for treating people with psycho-emotional problems, things that are in the subconscious memory, as well as physiological problems. Griffiths has treated clients for a wide range of issues, from phobias such as a fear of cockroaches or public speaking, to digestion and women’s issues.

“I have quite a few clients who are pregnant now. A lot of the time its just stress getting in the way – a lot of women spend years trying not to get pregnant, so it’s about removing that programming,” says Griffiths.

She and other practitioners at the centre are looking forward to having Krebs in town this month to give them some special training. He will also give a public lecture, workshops and be available for some private sessions.

Soon after his first kinesiology class, he went back to work as a research scientist, but quit in 1988 to develop his own particular type of kinesiology, Learning Enhancement Acupressure Programme, a programme to treat learning problems. He published a number of scientific papers and books, including A Revolutionary Way of Thinking and Nutrition for the Brain and he is co-author of Energetic Kinesiology, the first systematic presentation of energetic kinesiology as a field of study.

His work as well as that of other kinesiology practitioners is helping to bring kinesiology into the mainstream. He’s currently overseeing a project at Harvard University that will document the positive effects of kinesiology on the brain. Getting funding for such work isn’t easy and the project was funded by two generous supporters in Tasmania.

“Acupressure has been scientifically proven. We’ve known for some time that acupoints have electrical properties, but in the past year the Chinese have used a 3D MRI to show that acupoints on the skin are real things, there is a real structure to them. More and more kinesiology is being accepted as scientific,” says Krebs.

Original Link: SCMP