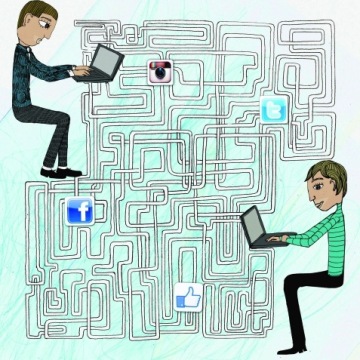

Left to their own devices

— December 2, 2014Social media and texting are here to stay, but youngsters shouldn’t let gadgets rule their lives, says developmental psychologist

Technology is a double-edged sword – in a short space of time it has given us unprecedented access to ideas and information, and connected us to people around the world.

But all this comes at a price, and it’s young people who are most affected by it.

Life online is affecting teenagers’ identities as well as their capacity for imagination and intimacy, says American developmental psychologist Howard Gardner, whose 2013 book, The App Generation explores adolescent life in the digital era.

But the most surprising finding from his research was that young people today are more risk averse; they are unwilling to take chances in case they make a mistake.

“Kids used to make up plays that weren’t very good. But they still made them up,” says Gardner, a professor at the Graduate School of Education at Harvard University.

“Now they just reproduce them from a smart device because it’s easier to do and slicker. But they aren’t using their imaginations – that’s what we’re talking about with risk aversion,” he says.

Studying drawings and writings created by children 20 years ago, and comparing them with recent works by children, Gardner and co-author, digital media specialist Katie Davis, found that their graphic productions were more imaginative, but their literary inventions were less creative.

Surprising, too, was the discovery that few young people get lost these days, because there’s always a device or an app on hand to guide them.

“This notion of everything being planned, one thing after another, is something which may become a source of stress,” says Gardner, who was in town last month to give a talk at the Asia Society.

Best known for his theory of multiple intelligences, Gardner doesn’t reject technology, but underlines the importance of being in control of it – being “app-enabled” rather than “app-dependent”. The risks of doing otherwise are significant.

Best known for his theory of multiple intelligences, Gardner doesn’t reject technology, but underlines the importance of being in control of it – being “app-enabled” rather than “app-dependent”. The risks of doing otherwise are significant.

Consider the issue of identity. Young people feel the need to package themselves, particularly for social media. Creating an impressive online profile might make them feel good momentarily, but that is eroded as they compare themselves to others on social media.

This emphasis on looking good on the outside makes them less likely to be able to share their anxieties, doubts and fears.

Another danger is the risk of what Gardner calls “premature primary identification”. This entails declaring who you are and being unwilling to change before you have the chance to explore other identities.

Rohan Bansal and Ivy Tse, both Year 12 students at Hong Kong International School, are well aware of the pitfalls of being overly focused on social media. Tse, who lists about 700 Facebook friends, recognises that web identities are illusory.

“My online profile isn’t a good representation of me. You can get two people in real life who are completely different and yet their Facebook profiles look similar,” she says.

Bansal has more than 800 friends on Facebook, but admits they aren’t all buddies. He says spending too much time on social media can be depressing, as he compares himself with his connections, who seem to be doing amazing things.

Bansal believes the emphasis on social media also affects his real-life friendships. “Emotions can get dimmed down on technology, and that can get carried into real life. If you talk online, it never seems as serious as in real life, and then when you do meet face-to-face that feeling gets carried over,” he says.

Too much time spent socialising online is detrimental, says Gardner. There is potential for misunderstandings, which lead directly to many break-ups online. Also, the fact that reactions cannot be observed leads to poor communication and ultimately to an erosion of social skills.

Some teenagers are very conscious of the nuances of real-life interactions. Tse, for one, tries to avoid using emoticons when chatting online because they can be confusing. “They are a kind of shorthand, and they are hard to interpret if you can’t hear the tone that the person is using. What does a smiley face mean? In real life there are so many types of smile.”

Gardner questions the trend towards having hundreds of “friends” but few genuine friendships built on trust and intimacy. This means young people have few people to share their fears and anxieties with, and are often unwilling to let their guard down.

On the upside, people who feel isolated, like those grappling with coming out as homosexual, are now able to connect with others who share their interests.

Gardner’s most recent, as yet unpublished, research looks at the students at US universities and colleges who are seeking help for mental health issues. “Often between 20 and 40 per cent of the students who come to college need to have support from mental health services. Nobody knows why,” he says.

The explanations range from the presence of a drinking culture, the use of prescription drugs and the way that students who are used to tutors lose that support when they start college. Gardner wonders whether the digital lifestyle may be to blame for this trend; it has certainly played a role in bullying.

“It used to be that when you went home, you wouldn’t get bullied. But unless you have the fortitude to keep away from your devices, you can be bullied all night long,” he says.

Marty Schmidt, a humanities teacher at Hong Kong International School who attended Gardner’s talk, is certain technology has a big role to play in the rising rate of depression among teenagers.

As his students’ digital lives have expanded over the past five or six years, so has the rate of depression, he notes. “To me, it seems obvious the two go together – being engrossed in technology can make kids feel emotionally fragile,” he says.

Schmidt, who runs an elective class for Year 12 called “Science, Society and the Sacred”, has been encouraging students to read sections of The App Generation for discussion. “My students expressed how they are really worried about technology, and how they are losing the ability to have face-to-face relationships. That surprised me, because I see them interact every day, and they don’t seem different to me.

“But obviously, they feel differently,” says Schmidt, adding that his 12-year-old son has told him he understands how easy it is to get addicted to technology.

Hans Ladegaard, a professor of English at Baptist University, says he has to remind his class not to use social media or send text messages during lectures.

“I have to keep repeating the message – don’t use Facebook in class. It is like a third arm or a leg, like a part of their body. The downside is that it affects their ability to concentrate,” he says.

There is an upside, though. Every class he teaches is accompanied by an online forum, extending the discussion beyond the classroom. Ladegaard finds that some students are much better communicating online rather than in class. This is an opportunity for those who might otherwise have remained silent to speak out.

“Young people seem to be controlled by the way they use technology. If they can’t live through a 50-minute class without checking Facebook, then technology is setting the agenda,” Ladegaard says.

That’s Gardner’s bottom line, too. Technology has so much to offer but when we allow it to dictate how we spend our time and what we do, then the advantage is lost.

This holds true for adults as well as children and Gardner urges parents to set a good example. It’s an opportunity for young and old to complement each other’s strengths.

While teenagers are often knowledgeable about technology, they might not have a good model for how to use it, or the wisdom to know when to put it away. Adults can help.

“It’s easy to think of a dystopia in which people give up even the illusion of free will by letting themselves be dictated by these devices and the options they involve,” says Gardner.

“Why bother to live if everything is just designed by some app maker? I think we have to develop the will muscle – what I call app transcendence – and put it away,” Gardner says.

For Schmidt, the “quantum leap” that has technology permeating every aspect of modern life is a blessing and a curse. “Technology is the archetype of fire – we know it is both wonderful and dangerous at the same time,” he says.

Original Link: SCMP