Who are you, Mr Loo?

— November 9, 2014Admired abroad and loathed at home, little was known about this secretive, cunning Chinese art dealer until a surprising find was made in 2006

Arguably the most important art dealer of the mid-20th century, C.T. Loo is revered in America and Europe but loathed in China. He introduced the West to China’s art but in the process looted the country of its finest works. Until recently, little was known about this wheeler-dealer beyond his most prominent achievements.

A secretive and cunning man with a genuine passion for Chinese art and love of his country, Loo was a womaniser with a complicated personal life. His road to professional success and the details of his romantic life we now know thanks to the painstaking research of Geraldine Lenain.

International head of the Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art Department at auction house Christie’s, Lenain was raised in Africa and moved, at the age of seven, to Hong Kong, where she attended the French International School. She would go on to earn a degree in art from the Sorbonne, in Paris.

Working as an Asian art expert in the French capital, she was familiar with the name C.T. (Ching Tsai) Loo. He enabled many of the world’s most prestigious museums and galleries to acquire exceptional pieces of Chinese art – the imposing 5.8-metre Sui stone sculpture in the British Museum was presented by Loo, and he helped the University of Pennsylvania, in the United States, secure its magnificent Tang-dynasty limestone statue. But unlike other leading art dealers, there existed no biography of this man, and no serious research had been done into who he was and what motivated him.

In 2006, Lenain received an intriguing phone call. A man claiming to be Loo’s grandson asked her to meet him at the Pagoda Paris.

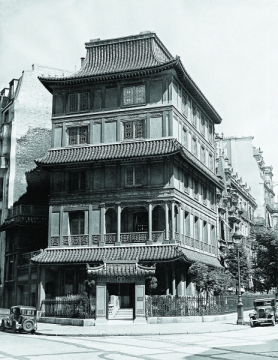

Most Parisians are familiar with the pagoda – walk through the 8th district of the city and you can’t miss it. Adjacent to Parc Monceau, the original building was remodelled in 1928 to look like a classic Chinese pagoda and painted red. Lenain was aware that Loo, who died in 1957, had been behind the iconic building and that it had served as his gallery and sometime home, but she had no idea it still belonged to his family. Assuming the caller wanted to show her a work of art – a ceramic or perhaps a painting – she turned up at the pagoda, where she was ushered up to the first floor.

“I was looking around for a piece, but there was nothing. And then the grandson, Joel Cardosi, said, ‘Here it is.’ I saw only very old and dusty cardboard boxes and, inside, old-fashioned files with correspondence and albums of photographs,” says Lenain.

The boxes had been found hidden in the basement, behind a cupboard, as the family was clearing the pagoda before putting it on the market. It didn’t take Lenain long to realise this was a treasure trove, containing 50 years worth of documentation about the personal and professional life of a secretive man. Thus began an eight-year project. She spent months wading through the material, got to know the family and became close to Loo’s then 92-year-old daughter, Janine, one of Cardosi’s aunts. She even travelled to Loo’s home village of Lujiadou, in Zhejiang province.

Listening to her speak about her research, it soon becomes obvious this project was more than a job for Lenain; for years it was her life and she even began to draw parallels between Loo and herself.

“We shared the same passions – art and China. I’ve worked and lived in the cities that C.T. Loo also lived in – New York, Paris, Beijing and Shanghai – so I understood what was in those letters,” says Lenain, who lives in Shanghai, with her diplomat husband and children.

She published the book Monsieur Loo – Le Roman d’un Marchand d’Art Asiatique ( Mr Loo – The Novel of an Asian Art Dealer) in French and Chinese last year.

“He is a chameleon. He changes his discourse and appearance depending on the person in front of him – when he was with Westerners, he never talked about China and Chinese friends. And when he was with Chinese, he never talked about his [French] family, his Western side, so no one knew the other side. He split himself completely in two,” says Lenain.

“He is a chameleon. He changes his discourse and appearance depending on the person in front of him – when he was with Westerners, he never talked about China and Chinese friends. And when he was with Chinese, he never talked about his [French] family, his Western side, so no one knew the other side. He split himself completely in two,” says Lenain.

Among his papers, Lenain came across an attempted autobiography, begun two years before his death. He said he wanted to leave a record for future generations but it soon became obvious from the rough draft that, rather than setting down the facts, he was instead trying to rewrite his life.

“He lied to everybody about everything – so what was he hiding? In the beginning, I planned to write a catalogue of all the pieces that went through his hands and were placed in museums and private collections, but going deeper into the research I wanted to find out why he was lying,” says Lenain.

The truth is Loo came from very humble beginnings. He was close to his mother, who toiled in the fields of Lujiadou. His father was an opium addict and a gambler. Loo was almost nine years old when his mother committed suicide. His father died soon after.

“I think he was deeply affected; he was very, very sad, but he showed no emotion. He wanted to take revenge in life. Why did he lie? It’s not a shame to have started from nothing and to have come to the top. On the contrary, it’s very good – it means you have worked hard and are intelligent. But he was ashamed of his low background and his mother’s suicide,” says Lenain.

Having spent eight months looking for it, Lenain visited Lujiadou, in countryside 2½ hours outside Shanghai. With just 200 inhabitants, it’s as small today as it was 150 years ago. The plan had been to see where he grew up and get a sense of the place but, after a little digging, she met some of Loo’s relatives, who no longer live in the village. It was the most emotional moment in her research and, she says, she cried as they produced paperwork to show that every year until 1956, just before he entered hospital, he wired US$2,000 back to Lujiadou.

“Those heirs didn’t know who he was or what he was doing. They knew the money was made in the West but they never asked questions, they were ignorant of his business,” says Lenain.

“He was very proud of his country. When the Japanese were in China, in 1937, 1938, he did what he could to send money to mobilise people to fight. He did the same thing when the Communists arrived; he was giving a lot of money to Madame Chiang Kai-shek. He said he loved his country but … at the same time he looted it for 50 years.”

LOO WAS 15 WHEN HE started working as a cook for the wealthy family of diplomat Zhang Jinjiang in Huzhou, Zhejiang province. Seven years later, in 1902, Zhang was posted to France and Loo accompanied him. When the diplomat opened a shop selling Chinese porcelain, carpets, lacquer and silk in Paris, Loo became a sales assistant. In 1908, he set up his own gallery in the French capital.

This was a time when the West was fascinated with chinoiserie and collectors were looking for 18th- and 19th-century porcelain. Loo dealt in those pieces to begin with because they fetched high prices. He began by sourcing items from other dealers in Europe but, within a few years, he’d set up offices in Beijing and Shanghai. And he soon began exporting much bigger, better quality objects: huge sculptures and frescoes. This was a new market and Loo’s success was in educating European and American collectors about what they were buying.

“He applied vocabulary and chronological systems that Westerners would understand. The classical period, the baroque period; this is how we in the West determine the period of art, so he applied that vocabulary to Chinese art. It had never been done before and it was a great success,” says Lenain.

Loo quickly became a big player in the art world.

“He single-handedly changed the way the West perceived China,” says Julian Siggers, director of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. “By enabling Western museums to build these collections, he fostered a great deal of interest in the scholarship of China. These are the collections that will prompt art historians to become Sinologists.”

Loo knew what Western collectors wanted and he had the men on the ground in China to fulfil those demands. He became the dealer people turned to when an important piece became available.

“Some pieces were still in the temple, on site; very heavy sculptures. So before taking the risk of digging it out and finding no buyers these people were actually taking pictures of the sculpture still in the temple and saying, ‘Are you interested?’ And if yes, they would dig it out,” says Lenain.

Loo invented a code; there was no point sending a telegram in French or English to partners in China who couldn’t read those languages, so he devised a dictionary whereby each city and word to describe an artwork was given a specific letter.

Loo was just as creative – and clever – in his romantic life. He had an affair with Zhang’s wife that lasted more than a year. He lavished her with gifts and set up secret rendezvous by using postcards. The image on the card and the placement of the stamp indicated the location, date and time of a meeting.

When he set up his own gallery, he met and fell in love with Olga Libmond, a beautiful Frenchwoman who ran a hat store next door. Roughly the same age as the 30-year-old Loo, Libmond was to become the love of his life, but they never wed. Instead, Loo married her daughter. This may sound like a bizarre set-up, but in Loo’s world it made perfect sense. Libmond was receiving money from another man and if she had married Loo, those funds would have stopped. It was Libmond who came up with the plan for Loo to marry her 15-year-old daughter, Marie-Rose, so they could stay together and still keep receiving the additional money.

“He was thrilled. He had tried very hard to have Western girlfriends and now he had two for the price of one,” says Lenain.

Marie-Rose was uneducated and knew little of the world. It was Libmond, with her strong personality and business sense, who Loo trusted with his business affairs; she had the code to the safe in his Paris gallery. Marie-Rose gave birth to four daughters but the fact she never bore Loo a son didn’t help the marriage.

“I’m very sad for Marie-Rose because the pictures through their life show Olga and C.T. Loo always together or, when they are walking, then the wife behind, a bit apart. If you didn’t know, looking at the photographs, you’d think it was a couple with someone from the family next door,” says Lenain.

The youngest of Marie-Rose’s four daughters was Janine. She had never got along with her mother, who died in the 1980s, and, when Lenain began her research, she had only recently found out why.

“When Janine was born she was a huge disappointment because she was a girl. It was [Marie-Rose’s] last chance to get her husband back – if she didn’t give her husband a son she would lose him forever. After Janine was born [Marie-Rose] was operated on, so she knew she couldn’t have any more children,” says Lenain.

Janine passed away two weeks after the book was published. She had managed to get to the 70th of 200 pages.

“It was a relief for her that the life of her father was put in the light; somewhere the truth is out,” says Lenain.

Although she has succeeded in filling in many of the holes in Loo’s life story, Lenain says she is still discovering information. She refers to two “important documents” that are proving elusive.

“I know very important information that will move forward the research, but China may not be ready to give me access. Maybe in a few years they will feel more comfortable,” says Lenain.

Chinese discomfort, of course, lies in the fact that Loo is seen as a thief of national treasures, but “this is a story with two sides”, says Siggers.

“I would urge people to look at it in the context of the world 100 years ago. He did China a great service by bringing these pieces to the West,” says the museum director, suggesting that had they been left in China, the works of art might have been destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.

Of course, Loo couldn’t have anticipated the Cultural Revolution. He died a decade before it began and his business had collapsed eight years before that.

In July 1948, as the civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists was reaching a peak, Loo received a telegram saying that an important shipment containing a number of national treasures had been stopped by customs in Shanghai. A year later, the Communists were in power and Loo and his business partners were deemed counter-revolutionaries. With a death sentence hanging over him, Loo escaped China, but many of his close colleagues and friends met tragic ends. Some were killed outright, one had to jump out of a window and another died after 19 years in a labour camp.

In 1951, Loo, claiming to be financially ruined, prepared his last catalogue. He usually asked a scholar to write the introductions, but for this liquidation catalogue he wrote the preface, attempting to defend himself.

“He explained that he was actually trying to help China by bringing Chinese sculpture and objects to the West; that he was an ambassador for China. He even added that if the pieces had remained in China perhaps crazy people would have destroyed them,” says Lenain.

Lenain gives occasional talks about Loo. On the mainland, the focus of post-talk questions is always on the looting and repatriation of artworks.

“Maybe one day he will be rehabilitated, but today it’s too soon; he’s still seen as evil,” says Lenain.

Original Link: SCMP