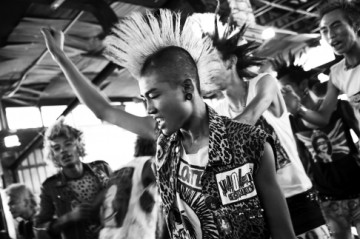

Mohawks in Myanmar

— April 7, 2013Although closed off from the world for 50 years, the reclusive Myanmar still developed a punk rock scene

Kyaw Kyaw is angry and he’s got attitude, but he’s not like the young punks who came before him. He and his entourage say more about what’s happening in Myanmar today than they do about music.

Closed off from the rest of the world for 50 years after the military junta took over in 1962, Myanmar’s punk scene was a late developer. Sid Vicious was dead, his ashes scattered over girlfriend Nancy Spungen’s grave, 15 years before his music came to Yangon, brought in by the sailors who were among the few foreigners allowed into the country.

“There’s only one guy still around from that time – a first-generation punk,” says Darko, lead singer in the indie rock band Side Effect. “He’s still a punk and he runs a stall in the market.”

“There’s only one guy still around from that time – a first-generation punk,” says Darko, lead singer in the indie rock band Side Effect. “He’s still a punk and he runs a stall in the market.”

At this kiosk-sized stall just out of town in Yuzana Plaza, 40-year-old Ko Nyan, the last of the original Myanmese punks, makes a living selling punk T-shirts and CDs. He was 21 when he fished a music magazine out of the bins at the British embassy and saw an article about the Sex Pistols. It changed his life. He didn’t just want to play punk music, he wanted the whole lifestyle and he and his friends shocked Yangon with their edgy look.

“In those days things were really bad,” says Darko. “You could get thrown into jail over nothing. The police used to pick up the punks and beat them up for no reason, and shave off their hair.”

Thirty-two-year-old Scum knows what it is like to be hounded by the police. He was nine years old when he first got into heavy metal music. “There were only two shops in Yangon that sold Western music and I’d go there every day and buy at least one cassette,” he recalls. “I had to steal the money from my mum or borrow from friends. It was like a music addiction.”

Later he developed another addiction – this time to heroin. But that didn’t stop him studying literature at Yangon University of Foreign Languages. It was there, in his final year in 2003, that he formed a band called Diehards.

“When I said I was going to form a punk band just like in Europe, people said it was impossible. They didn’t think I could do it, but I did. It was a hardcore punk band, the first in Myanmar,” says Scum.

Even by Western standards, Myanmar’s early punk scene was hardcore. Many coloured their hair using the aerosol canisters favoured by graffiti artists and during the Water Festival, Myanmar’s party season, they went to extremes to make sure their hair stayed spiked.

“The punks used glue for sticking down leather to stick up their hair. You couldn’t get that glue out, so after four days of partying at the Water Festival they had to shave their hair off. I didn’t do that because I dressed like a punk every day, not just for the festival,” Scum says. Before his final-year exams, the police caught Scum with a joint’s worth of marijuana and he was given a 12-year sentence. He served six years: three in the notorious Inseine Prison and the rest in a labour camp.

The conditions in Inseine Prison were hellish, with 100 men crammed so tightly into a cell the “nobodys” didn’t have enough space to sleep on their backs and had to lie on their sides jammed up against the others. But Scum survived. He bribed a guard and smuggled in needles and ink to set up a small tattoo business. His upper body and arms are covered in tattoos – there’s one on his neck and the word “punk” is inked into his knuckles.

The conditions in Inseine Prison were hellish, with 100 men crammed so tightly into a cell the “nobodys” didn’t have enough space to sleep on their backs and had to lie on their sides jammed up against the others. But Scum survived. He bribed a guard and smuggled in needles and ink to set up a small tattoo business. His upper body and arms are covered in tattoos – there’s one on his neck and the word “punk” is inked into his knuckles.

The business earned enough to feed his addiction.

He was still behind bars in 2007 when thousands of monks took to the streets in what became known as the Saffron Revolution. Students and political activists joined the movement until a bloody crackdown that September. In the same year, Kyaw Kyaw formed his band, Rebel Riot.

“Kyaw Kyaw?” scoffs Scum. “He’s no punk, he’s just a poser. He and those guys just dress up and take photographs and post them on Facebook. They convince the Westerners they’re punks and live the life of punks, but they’re not into hardcore punk. They’re just in it for the fashion.”

There’s a little media huddle around Kyaw Kyaw’s punk shop on Sule Pagoda Road. In between selling punk T-shirts, Kyaw Kyaw flits between two German journalists, a French photographer and this writer.

“Why are all these foreign journalists so interested in us?” Kyaw Kyaw says, clearly loving the attention yet genuinely baffled.

It’s a fair question. There are little more than 100 punks in Yangon now, but they’ve been garnering a good deal of press attention. That has a lot to do with the wave of journalists who have flooded into Myanmar in the wake of the sweeping reforms. They’re all after stories and on the surface Yangon’s punk scene is a simple one: angry young men rebel against an oppressive military regime. Except it’s not quite that simple anymore. The story has moved on in the past few years and the punk scene is evolving, as it did in the West.

The genre attracts fans to events such as the Burma Punx Festival and the I Am Legend concert, both held in Yangon.

Kyaw Kyaw and his band haven’t played for some time – he’s vague about the next date and doesn’t know whether Rebel Riot might even play again. He blames the lack of venues. Instead he’s focusing on his new business – his Sule Pagoda Road punk shop has been going four months – and fending off journalists.

“I’ll give you an interview, but first you must make a donation to my foundation,” he says. Even the photographer is told he can’t take a snap without paying first. Media ethics are briefly discussed. Kyaw Kyaw listens, nods, but insists on a “donation”. There is no interview.

But back to Scum, who is getting edgy. His hands are shaky – he’s on methadone and has been clean for a year. “I don’t think the punk scene in Myanmar is developing. Actually, it’s going backward and the punk bands here now can’t play and they can’t sing for s***,” he says.

There were about 400 punks in Yangon in 2000, he says, but only a quarter of that number now. Why are the numbers falling? Could it be that with the new government there’s nothing to rebel against any more? Scum puts paid to that suggestion fast.

“The government is no different from the old one. We have press freedom, but that’s all. There’s nothing for the welfare of poor people, nothing has changed for the lower class.”

He blames the decline in the Myanmar punk scene on competition from another musical subculture: hip hop. “Everyone loves it, even old women and young children,” he says.

Yangon-based photographer Matt Grace agrees. “Hip hop music is more popular and more commercially viable. They can get more money for recording.”

Grace has been following Yangon’s music scene for a few years and says it is commercial realities that are hurting the punks. “The underground scene is held back by the fact they can’t play live on a regular basis. If they can’t play live, what’s the point?”

Scum is determined to hold true to his punk roots. Last year his band, Kultur Shock, released an EP titled Dark Future, and he plans to release another later this year, but he’s not hopeful for the Yangon punk scene which is beginning to look as though it might be treading the same path as the punks in the West.

“When we were young, punk was rebellion. Now it’s f***ing fashion,” he says.

Original Link: SCMP

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/027-SCMP-Burma-punks1.pdf]

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/027-SCMP-Burma-punks2.pdf]