Building expectations

— April 21, 2013The winner of this year’s Pritzker Prize, Toyo Ito tells Kate Whitehead that the 2011 Tohoku earthquake taught him a great lesson and explains why architecture must be felt with your entire body

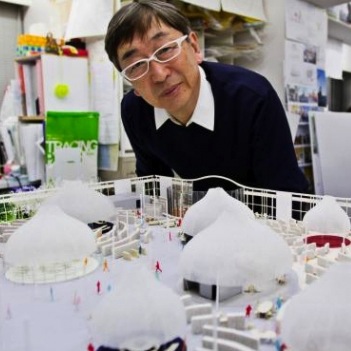

Toyo Ito has been so busy he’s barely had time to celebrate. When the Japanese architect received the news last month that he’d won the Pritzker Prize, he and his team were putting the finishing touches to their concept design for M+, the museum of visual culture planned for Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District.

“We stopped for a little drink upstairs and then went back to work,” says Ito, sitting in his Shibuya office, in downtown Tokyo.

A heady fragrance fills the room, from baskets of purple and white orchids sent to congratulate the sixth Japanese person to receive the prestigious award.

The judges praised Ito for combining conceptual innovation with superbly executed buildings. He’s best known for the Sendai Mediatheque, a seven-storey glass box of a library that opened in 2001 and put him on the international map. Other standout works in Japan include the Tower of Winds (1986), in Yokohama, the Matsumoto Performing Arts Centre (2004), in Nagano and Italian shoemaker Tod’s Omotesando Building (2004), in Tokyo. Outside Japan many will be familiar with the Serpentine Gallery (2002), in London, VivoCity (2006), in Singapore and the National Stadium (2009), in Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

The 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami spurred Ito and other Japanese architects to develop the Home-for-All project, creating communal spaces for survivors.

Over more than 40 years, Ito has amassed a huge body of work – and winning the Pritzker might be considered the crowning glory – but he shows no signs of slowing down. Slim and trim – he walks his dog for an hour every morning – he’s a young looking 71-year-old and his practice is buzzing. Ito’s Tower of Winds, Yokohama.

“I started in 1971, when Japan was in the midst of change,” says Ito. “In the 1960s, architects were mostly interested in making buildings which conveyed the image of futuristic cities but, by 1971, people were becoming more inward looking, taking a more oppositional and critical stance.”

This goes some way to explaining why he isn’t known for any particular style.

“I want to move on from the kind of refining of borrowed things that [has] characterised Japanese culture since so long ago,” he says. “I’m not interested in having a signature style; I don’t want to repeat myself. In terms of the architectural profession I may have put myself at a disadvantage because of this, but every project is moving on from the last.”

So his work is an evolution? “Yes, sometimes – but not always,” he says, chuckling.

Ito shares those qualities of lightness and calmness that are so often attributed to his buildings. He’s not afraid to laugh at himself – or even, after so long in the business, to rethink the very fundamentals of modern architecture. Among the first architects to respond to the 2011 disaster, he says it led him to start from zero and consider the very basics: what is architecture; who are we building for?

Ito shares those qualities of lightness and calmness that are so often attributed to his buildings. He’s not afraid to laugh at himself – or even, after so long in the business, to rethink the very fundamentals of modern architecture. Among the first architects to respond to the 2011 disaster, he says it led him to start from zero and consider the very basics: what is architecture; who are we building for?

He’s also been thinking about cities recently – big Asian cities in particular, such as Tokyo, Hong Kong and Kuala Lumpur – and says we can no longer assume that their continued growth is something to celebrate. To better understand where that position comes from, and Ito himself, you need to consider his own story.

Born in Seoul, South Korea, to Japanese parents, Ito was two years old when, in 1943, he moved to Japan with his mother and two elder sisters. His father followed two years later, just after the second world war, and they lived in his father’s hometown in Nagano prefecture, northwest of Tokyo. His father died when Ito was 12 and the family moved to Tokyo, where he attended the prestigious Hibiya High School.

Tokyo in the early 50s was only just beginning to get back on its feet. It had suffered terribly in the war; more than half of it had been flattened, and the rebuilding process was slow to get underway.

Ito’s father had often sketched plans of friends’ houses and later, in Tokyo, his mother commissioned the early Modernist architect Yoshinobu Ashihara to design their home, but Ito didn’t give architecture much thought as a youth. His great passion was baseball.

Hibiya High School fielded some of Japan’s best student players. “I was on the school team,” he grins, with some pride.

It was only when he started at the University of Tokyo that he became interested in architecture. He submitted a proposal for the reconstruction of Ueno Park for his undergraduate design diploma and bagged the top prize. After graduating, in 1965, he went to work for prominent architect Kiyonori Kikutake.

The five years Ito spent at Kikutake’s practice gave him the confidence to set up his own studio.

“Kikutake taught me something wonderful. He said, ‘When you look at a building and try to assess it, don’t just think logically, think with your whole body.’ I’ve been treasuring that ever since,” says Ito. He has passed that wisdom on and devotes considerable time not only to nurturing talent among his own team but teaching at universities and, more recently, setting up a design school, Ito Juko.

“I often tell my staff, ‘If you think just with your head then that feeling may change in three days, but if you think with your whole body then you can really trust your assessment,'” says Ito. “I want my staff to learn to trust their intuition. I’m often hoping, looking out for the special magic of the creative feeling.”

Having designed houses, parks, libraries, theatres, shops, office buildings, pavilions, a kindergarten, a fire station and a community centre for the elderly, the projects he most enjoys working on, he says, are public cultural facilities. On such projects, his meshing of creativity with practical considerations shines. It’s also an area, he says, where the government has somewhat narrow-minded, pre-conceived ideas about what buildings and spaces should look like.

“It’s possible to use older models when designing a home, and the continuity in lifestyles means that people can still be comfortable living in them. But culture and the arts are constantly changing. It’s impossible to stick to old models for cultural facilities and expect them to be appropriate for what creators want to do now or what audiences expect. But that’s what the bureaucrats usually insist on.”

The success of the Sendai Mediatheque was down to a lucky break. When an open competition was launched for the project in 1995, there were no government officials on the judging panel and the top judge was an architect. Of course, government officials had to give final approval, but a crafty name change smoothed the way. The officials knew exactly what a library should look like, but a “mediatheque” was something different and there were no rules.

“It was a made-up name – and it helped us get around the bureaucratic mindset,” says Ito.

As is often the way with change in Japan, once the Sendai Mediatheque proved a success, it paved the way for further progress.

“It had a big, positive effect on the community. They enjoyed using it and it enhanced their life and the bureaucrats changed their mindset, too,” he says.

There have been plenty of other libraries and cultural projects since then but, for Ito, nothing came close to the Sendai Mediatheque until his proposal for a cultural complex in Gifu City, west of Tokyo, won a competition in 2011. Work will begin on the complex this summer and should be finished next year. A large layered model of the project dominates the centre of his studio space.

“It will use half the energy of Sendai Mediatheque,” says Ito, removing the top layer of the model and explaining how underground water will be used to heat and cool the complex.

Environmental issues and sustainability are key concerns in his current design concepts. Due for completion next year, the Market Street office tower, in downtown Singapore, will be a 40-storey building decked in green, with a “sky forest” on the roof. With cooler temperatures at the top, cooler – and cleaner – air will be pushed down through the building.

Then there is his proposal for the West Kowloon project. Ito was invited to submit plans for the 60,000-square-metre museum, along with five other international design teams.

Reluctant to give away too much about his design at this stage, Ito does reveal that a key feature would be a large indoor/outdoor space, a covered area allowing air to circulate and eliminating the need for air-conditioning. The winner will be announced in the summer and if Ito gets the contract, it will be his first Hong Kong project.

The six shortlisted architects were invited to Hong Kong recently for a workshop with museum staff about their design proposals.

“I’ve done many proposals and this was the first time I’ve experienced this kind of element, where I got to talk to the people who will be using the building,” says Ito. “I was very impressed.”

Interaction with the end-user has been on his mind since the 2011 quake. As with many who headed to the disaster zone to offer assistance, the experience had a huge impact on him and his team.

“Some of my staff stayed in temporary housing with the evacuees for a month and when they came back they were transformed; all of them who went there,” he says.

Soon after the quake, Ito visited the devastated region to see what could be done to help. He wasted little time in establishing the Home-for-All project, to create shared spaces where people could relax and begin to talk about the future. He pulled in some of his peers – Riken Yamamoto, Hiroshi Naito, Kengo Kuma and Kazuyo Sejima – to work with him; and, so far, four of six planned “houses”, each designed by a different architect, have been built, including Ito’s.

The process of spending time with survivors, talking to them and assessing their needs led to a fundamental shift in his thinking.

“I realise it’s no longer enough to just make something and give it to people. The people who use it need to be involved from the beginning. That’s the only way to make places people want to feel part of,” says Ito.

During a 2009 lecture at Princeton University, in the United States, he said that while nature was complicated and variable and built on what he called a “fluid world”, architecture strived to establish a stable system. He pointed to the grid system common in cities as an example, arguing that while it enabled a lot of buildings to be created in a short time, it also made the world’s cities homogeneous, which in turn made their citizens more homogenous.

“By modifying the grid slightly I have been attempting to find a way of creating relationships that bring buildings closer to their surroundings and environment,” he said.

Four years on and Ito offers more damning criticism of the world’s large cities, particularly those in Asia: “The era when we consider the continued growth of big cities a good thing is over,” he says.

Having lived in Tokyo for some 60 years, Ito has seen it rebuilt from scratch, flourish and, like other world cities, become a centre for cultural exchange. But now, with populations ageing, he sees the pendulum swinging the other way.

“Big cities will no longer be the most attractive place to live or the most interesting culturally,” he says.

But that future may be a long way off. For now, Ito remains intent on making big cities – including Hong Kong – more pleasant places in which to live.

Original Link: SCMP

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/045-SCMP-Toyo-Ito1.pdf]

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/045-SCMP-Toyo-Ito2.pdf]

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/045-SCMP-Toyo-Ito3.pdf]

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/045-SCMP-Toyo-Ito4.pdf]