As luck would have it

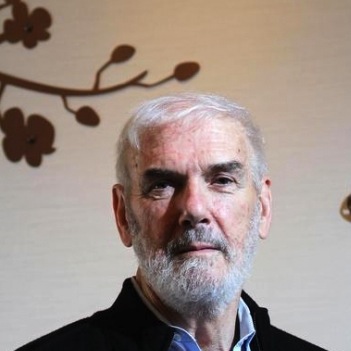

— July 21, 2013Jonathan Spence – historian, intellectual and eminent China scholar – is not one for a snappy answer.

He’s not slow to reply; just very thorough. Unhurriedly he paints a picture, sketching in plenty of detail and planting his response somewhere in the middle.

Ask him when he first became interested in China and he won’t give you a hard and fast answer. He’ll talk about his childhood, about his first conscious memory, and then go on to ponder whether we can even be certain that a memory is genuine. He’ll want you to understand the context behind what he’s saying – and it will always be interesting. Perhaps that’s what sets him apart from other historians – this knack of spinning his web and drawing you in.

In town to deliver University of Hong Kong’s inaugural Second Century Lecture and address an event at the Hong Kong International Literary Festival, in May, he looked every bit the distinguished professor. At 76 he has a full white beard and a head of hair to match. Despite having lived in the United States for almost 50 years, he hasn’t lost his British accent or dry humour. It’s easy to see how he must have charmed the Americans when he arrived at Yale University in 1959. They quickly took to him and he was a firm fixture on campus until he retired, in 2008.

Born into a lettered family and boarding school-educated from the age of seven, his was a privileged and peaceful childhood despite the war years. His father had attended Oxford and Heidelberg universities and spoke fluent German, his mother was a passionate student of French literature and the interests of his three siblings covered the classics and French, German and Italian translation.

There was very little in the first 20 years of his life to hint at the abiding interest that would drive his career. But Spence is a man keenly aware of the complexities of the human condition, and has done some serious navel gazing, wondering where his great passion for China came from; when it began. And he thinks he can trace it to a trip to the cinema with his father in the early 1940s, when he was five or six years old.

He remembers it clearly: it’s the second world war, a rare visit to the movies to see an early Disney film, Dumbo or Snow White, and there is a short news reel before the film starts.

Emperor Kang Hsi.

“What I recall vividly – which I think is the most accurate memory I have of this – is that in the news there was a clip explaining that some people were building a Burma Road. The announcer said that these people have built a road with their own hands to get around the Japanese army and bring strength back to China,” says Spence.

He gazes over the hotel suite and you sense he’s no longer in the Peninsula but back there in the dark of the cinema with his father.

He gazes over the hotel suite and you sense he’s no longer in the Peninsula but back there in the dark of the cinema with his father.

“I found this very powerful – the idea of people building a road through mountains with their bare hands, that image stayed with me.”

Spence is a very visual man. It’s more than a matter of appreciating aesthetics – he understands the clout that a powerful image can wield. What’s more, he has the knack of selecting an image that will make a profound impact. But before he fully realised this talent, there was boarding school at Winchester College to complete followed by two years of military service.

“I was in Germany keeping the peace – I always claim successfully because nothing happened when I was there,” he says of his post-war days in the army.

Having completed his National Service, he went to Cambridge University to study history, a subject he says he enjoyed more for the way it is written than any events that occurred in any particular place. No surprise then that in his second year at university he played with the idea of becoming a novelist, or perhaps a playwright. It was a short flirtation.

“When I realised that I couldn’t be a novelist it was because I didn’t feel I had enough to say. My life had been very organised; I’d been at boarding school from the age of seven in a somewhat bizarre English system and had gone into the army, not out of bravery, but because I was told to by my government and did two years National Service, [which he spent] mainly reading,” says Spence.

Chinese volunteers, including children, help to build the Burma road, which enabled supplies to reach Allied troops fighting the Japanese, in 1944. A news story of the event helped put a young Jonathan Spence on the path to Sinology.

He put down regular novels and picked up those of the historical kind.

“History was somehow something that gave me an anchor in, admittedly, other people’s lives,” he says.

It’s significant that first and foremost he sees the past made up of people, not just dates and places and treaties, and it is this approach that makes his books accessible to readers who are not especially interested in history, or in China. He even made it onto The New York Times bestseller list, though he’s quick to make light of this accolade.

The way Spence tells it, his publisher called him the day the book The Search for Modern China – an epic history of the country from 1600 to the present day – made it onto the list, delighted that the tribute could be added to the cover of the next print-run. It stayed on the list for weeks, during which time it also made the Canadian bestseller list.

“He called me up again,” recalls Spence, “and said: ‘Now we can call it an international bestseller!'”

Spence is far too grounded to let celebrity go to his head – although he concedes that he’s delighted each time the book is translated. The Search for Modern China most recently found its way into Turkish.

Having decided fiction wasn’t for him, he delved into history and never looked back: “I wasn’t prepared to generalise with no guidance at all. I wanted to have things shapeable. What was so clear to me in my second year in college was that one could really organise these events of the past in a different way.”

That’s not to suggest that stories aren’t central to what he does – they’re just real-life ones. He describes that special moment, the chill down the back of his spine, when he recognises the thread of a great story and is awed by the incredible sequence of events in which history is unravelled.

The way Spence tells his life story, luck played a big role in his success, too. Take the scholarship he was offered as he completed his degree – an exchange programme between Yale and Clare College, Cambridge. It wasn’t even one he had applied for: it came by way of an invitation. And it was only after he arrived at Yale, on his first trip across the Atlantic, that he decided to study China. Yale had a whole section with scholars dedicated to Chinese history, literature, politics and economics. The holistic way the culture was studied appealed and he immediately took to the husband and wife team of Chinese historians Mary and Arthur Wright.

Then came another lucky break. An anonymous donor offered a fellowship in the area of Chinese studies – did he want to use it and go through to a PhD? He jumped at the chance and chose to study in Australia, with Fang Chao-ying, a scholar who had fled China in 1946.

“Mr Fang realised that communist China was not going to be for him, nor was the Republic of China under Chiang Kai-shek, nor was Hong Kong with its British presence,” says Spence. “The one place for him was Australia.”

He spent a year in Canberra, at the Australian National University, meeting Fang weekly to read and discuss 17th- and 18th-century texts from im-perial China. It was a period of intense study and the more he learned the more fascinated he became. And this is where he got really lucky. When the nationalists fled the mainland, they took with them imperial archives. Fang just happened to be friends with a scholar who had recently been made the director in charge of the archive in Taiwan. Although the records weren’t open to the public, there was a chance Spence, who had begun to learn to read Chinese at Yale, might get to see them.

Fate was on his side again and he was given an extension of his grant to go to Taiwan. It was 1962 and because an invasion of Taiwan was considered imminent, the archives were moved to a location in the mountains. The material hadn’t been organised or catalogued – it was just bits of paper crammed into boxes that had been carried along on the exodus from the mainland in the late 40s.

And so he found himself among the mountain archives holding the original records of Emperor Kang Hsi, who ruled China from 1661 to 1722.

“In the Chinese dynasty there is a word for ‘I’ which we can only translate posthumously as ‘I the emperor’ – it was a first-person pronoun that only one man in the world was allowed to use,” says Spence.

Noting the use of this pronoun, he realised that these weren’t just papers from the imperial court – they were documents the emperor himself had written. The fact that they were written in red ink, and that the emperor was the only person allowed to write in red, confirmed it.

Hearing Spence talk about this period is like listening to someone describing the beginning of a love affair – that first chance meeting. Incidentally, he did later have another Taiwanese love affair – Annping Chin, his second wife and a senior lecturer at Yale, is Taiwanese, although they met in the US. They both have two children from previous marriages.

The first Western scholar permitted to study the archives, Spence’s hard work paid off and Kang Hsi became the focus of his PhD dissertation. He knew not just the political but the personal, too. Kang Hsi was remarkable in that he had 56 children and a lot of consorts – “an energetic young man”. In fact, his children were so numerous that he sometimes referred to them by number, delivering orders such as, “I want to talk to No17.” But with such a vast brood came great woes.

“The problems with his children were legion. I remember thinking how strange it was that a man could be the son of heaven and you could control everything in the country except your own kids. Several of his sons were killed by [their own siblings]. And there we are getting near a story – why encourage some of your children to kill others of your children?” says Spence.

His PhD was published in 1965 by Yale University Press and won an award, mentor Joseph Levenson declaring: “Qing historical studies will never be the same again.” A year later Spence joined the Yale faculty as an assistant professor of history and reworked his dissertation material, making the bold move to write the book as the emperor’s story.

“I persuaded Kang Hsi to think beautifully about his past,” jokes Spence and, in 1974, the book Emperor of China: Self-Portrait of Kang Hsi was published.

Having dedicated years to studying a man who exercised absolute power, he decided his next subject would be the opposite of that – someone with no power, who couldn’t shoot a reflex bow, who didn’t get the chance to travel. A woman.

Again, he stumbled across his subject quite by chance. On a trip back to Britain he visited a former professor at Cambridge and, killing time, dropped into the library. As luck would have it, the cage that held the university’s special collection of Chinese books – the Wade Collection – was unlocked.

“I reached up and took a book on the administrative cases of the early Qing. I opened it at random and found myself reading about a woman in the early Qing in Shandong province who had been murdered for running away with another man,” says Spence.

He knew he had found the complete antithesis of Kang Hsi. Unlike with the emperor’s story, he didn’t have enough material to do a first-person account, although he did manage to find the woman’s autopsy report, which had been kept by a magistrate in the 1690s.

The Death of Woman Wang became a book about rural China and a woman’s fate amid depravity and poverty.

“It’s probably my best book – it’s still available, so she still lives, which is a romantic view of history,” says Spence.

He’s written more than a dozen books on modern China but per-haps the one he’s best known for is The Search for Modern China, now in its third edition and widely used as a university text book, although it wasn’t written as one. Surprisingly for a historian who had been inspired by a secret mountain archive in Taiwan and a caged collection of 17th-century texts, The Search for Modern China was written in a pizza parlour.

Naples Pizza is located between the Yale campus and a car park. The attraction for Spence was that there were few distractions – no phone, no students and no faculty to disturb him. Once he’d negotiated a deal with the owner, Joe – he had to clear out during the busy lunch period – he was assured a quiet table at the back at which to write.

The Search for Modern China was published in 1990 and not long after he finished the manuscript Joe died.

“His wife, Rose, is still running the place,” says Spence. “There’s a newspaper article about me, ‘the pizza writer’, laminated and behind the till.”

Spence isn’t one for predicting the future and avoids being drawn into conversations about where China is headed.

“I don’t know, I’m not a seer,” he says.

Besides, there’s still so much of the past that’s coming to light. Take the Great Leap Forward and the subsequent famine – of the tens of millions of people who perished, Spence says, new studies suggest many of the victims were children.

“That’s just heartbreaking. I’d written the whole of Woman Wang but I’d never thought that the victims of the Great Leap Forward just died at the age of three or four or five,” says Spence, looking away. “There’s something very powerful in that image – I don’t know how it would work.”

And, unbidden, he’s doing what comes naturally – searching for the image that will bring cold statistics to life, putting the human element into history.

Original Link: SCMP

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/064-SCMP-Spence-1.pdf]

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/064-SCMP-Spence-2.pdf]

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/064-SCMP-Spence-3.pdf]