Olivia Chow says immigrant past made her stronger

— April 27, 2014As Hong Kong-born Olivia Chow takes on Rob Ford in the battle to be mayor of Toronto, she tells Kate Whitehead how surviving as a poor immigrant in Canada has steeled her for the fight ahead

She threw down her challenge six weeks ago and already the mud is beginning to fly ahead of the October 27 election – but Chow appears well-equipped for the battle.

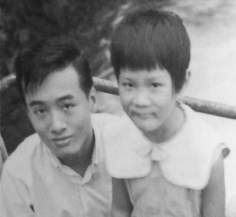

Born in Hong Kong to an education consultant father and a mother who was a teacher, Chow moved to Toronto in 1970, at the age of 13. The family wanted to leave behind the turmoil being sown in Hong Kong by political forces from the mainland, which was in the throes of the Cultural Revolution. From a comfortable home on Blue Pool Road, in Happy Valley, they found themselves struggling at the bottom of the ladder. Chow’s mother went from having a live-in helper to doing other people’s laundry.

Born in Hong Kong to an education consultant father and a mother who was a teacher, Chow moved to Toronto in 1970, at the age of 13. The family wanted to leave behind the turmoil being sown in Hong Kong by political forces from the mainland, which was in the throes of the Cultural Revolution. From a comfortable home on Blue Pool Road, in Happy Valley, they found themselves struggling at the bottom of the ladder. Chow’s mother went from having a live-in helper to doing other people’s laundry.

The transition was hardest on Olivia’s father, who took his frustrations out on his wife by beating her.

Life at home was tense and the teenager grew up fast.

“The problems we had when we first moved to Toronto; that’s what made me who I am,” says Chow, speaking over Skype from her kitchen in Canada’s most populous city during the first in a string of snatched conversations.

Her hair is wet from the shower, the phone interrupts regularly and there is the whirr of the printer as it spits out the speech she must give in 30 minutes across town, but she is determined to give the interview, she says, even if it means doing so in instalments over several days. The vast majority of Hongkongers might not be able to vote for her, but she cares what we think.

Chow wears a lot of yellow, her favourite colour. It’s the colour of hope, happiness and creativity, qualities the 57-year-old has in buckets. It’s also associated with intellect, communication and confidence, attributes she has honed over almost three decades in politics.

She was wearing a yellow dress the day she caught the eye of Jack Layton. Their love story is the stuff of legend in the halls of the Toronto City Council – a conscious coupling that would make them the city’s most powerful political couple.

But before Chow found love she had struggled through some difficult years as a new immigrant. Far from being an anomaly, immigrants are the norm in Toronto. According to Statistics Canada, in 2011, 46 per cent of the city’s metropolitan residents were foreign-born. Many – like the Chows in the 1970s – would have arrived with big dreams for the future only to be faced with even bigger challenges.

“I was digging through the family photos not so long ago – there were lots of pictures from 1970, when we first arrived. I remember one where we were in a park looking so full of hope. But from 1971 there were no photos,” Chow says.

Olivia lives with her elderly but still very active mother, Chow Ho-sze, and she asked her why there were no pictures after that first year. Her mother explained that life in those early days was very hard; it simply wasn’t worth recording.

In January, Harper Collins published Olivia Chow’s memoir, My Journey, in which she speaks frankly about life in the family household: “My father had been beating my mother even before I was born, but these beatings now escalated as new strains and pressures rocked them both.

My father had been managing his life quite well in Hong Kong, despite the irrational anger that darkened the home front. But now, in that eighthfloor apartment in St James Town, faced with disappointment and shame, his fury boiled over … and my mother bore the brunt.”

One night he smashed a lamp on her mother’s head while she slept, leaving a terrible gash – “It’s a wonder he didn’t kill her.”

Still in her early teens, Olivia often put herself physically between her parents to try to stop them fighting, sometimes even having to pull her father off her mother. She rarely brought friends home.

Chow would meet her best friend, documentary filmmaker Nancy Tong, in the summer of 1977. Tong had just graduated from Toronto’s York University and Chow was at the Ontario College of Art and Design, studying animation and sculpture. They both applied for a summer job working on a media project to showcase the history of Chinese Canadians. Tong believes the project “planted a seed” in Chow’s political consciousness.

While the project brought them together, it has been a shared love of art and their similar backgrounds and goals that have kept them close over the years. A few months ago, they holidayed together in the Galapagos Islands to celebrate Tong’s 60th birthday.

While the project brought them together, it has been a shared love of art and their similar backgrounds and goals that have kept them close over the years. A few months ago, they holidayed together in the Galapagos Islands to celebrate Tong’s 60th birthday.

“We grew up in Hong Kong – it’s a comfortable place and we were very comfortable with our Chinese identity. But when you arrive in a city where you are seen as second class you come into a crisis and you have to work that out,” says Tong, a visiting associate professor at the University of Hong Kong. “As a child of an immigrant you have to grow up really fast.”

Tong was in her late teens when she left Hong Kong but Chow was only 13, and under a lot of pressure.

“Olivia had to be the translator for the family, open bank accounts, do everything that involved speaking English. She had to protect her mother from her abusive father. And all with no siblings,” says Tong.

Chow’s step-brother, Andre, 10 years her senior and from her mother’s first marriage, had long before been sent to the United States to study electrical engineering. After Chow’s parents’ own son died at just a few days old, her father had evicted Andre, then aged 12, from their Hong Kong home. Chow’s mother had secretly saved to send her eldest child abroad.

The knowledge that your parents have given up so much to move to a new country in search of a better life for you creates a huge amount of pressure, says Tong. She believes that’s the reason many immigrant children are high-achievers – they don’t dare disappoint their parents.

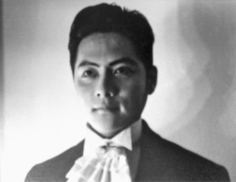

In Hong Kong, Olivia had been a rebellious student and often acted up in class. She failed Grade Three at Rosaryhill, on Stubbs Road, and was sent to Maryknoll Sisters School, on Blue Pool Road, just across the street from their Happy Valley home.

Maryknoll’s American Catholic nuns were known for instilling discipline and teaching good English, but they failed on both counts with Olivia, who was, by her own admission, the “hellion of the school”.

“I only understood half of what was going on at Maryknoll. I used to go home and watch Road Runner, Bugs Bunny, Batman and Robin and Mission: Impossible – that helped me with my English and to fit in when we got to Canada,” says Chow.

In her new home town, she attended Jarvis Collegiate, the oldest secondary school in Toronto.

“There were rich kids from Rosedale, second-generation immigrant kids from Cabbagetown and just-off-the-boat kids from Hong Kong, like me. About a quarter of the faces were Chinese,” says Chow.

Her experience as an immigrant has shaped her. In a recent campaign video she recalls desperately wanting a pair of ice-hockey skates, “because there was nothing more powerful, nothing more Canadian, than being able to play hockey. But those hockey skates had to wait, we could not afford them.”

Understanding the need to work hard for the things you want was an important life lesson, she says. Her mother worked first as a seamstress and, for a while, Olivia worked part time alongside her, sewing buttons onto blue jeans. And then her mother got a job in a hotel laundry, where she worked for many years. Olivia juggled two jobs in high school to help the family get by and her father took a number of low-paid posts – delivering Chinese food, then newspapers, and as a manual labourer.

Chow’s mother couldn’t speak English, so she wasn’t able to seek professional help in dealing with an increasingly unstable husband. It is telling that, years later, as a city councillor, Chow pushed for a multilingual emergency service. Today, the 911 service is offered in 140 languages.

Her father’s condition deteriorated until he suffered a mental breakdown and was admitted to a psychiatric ward. He was intensely paranoid and imagined people were trying to poison him. Doctors tried a number of therapies before they gave him electroshock treatment, which, combined with medication, prevented him from functioning normally. Today, he lives in a home and needs full-time professional care.

When she finished college, Chow wanted to put her experience to work by helping new immigrants. In 1979, she got her first taste of political activity, when she joined a rally in Toronto.

“The Vietnamese boatpeople [rally] was the first time I’d seen collective action. It was an awakening of mass movement. I thought, ‘Wow, I’m not the only one who thinks we need to do something. Look around me.’ That sense of power when you come to see the collective – that was my first experience of that,” says Chow.

She began working at WoodGreen Community Services, with Vietnamese refugees and Chinese immigrants. It was around this time that Chow met Dr Joseph Wong Yu-kai. Also from Hong Kong, he had studied medicine in New York and settled in Toronto in the late-70s. They met as volunteers planning an event for the Chinatown neighbourhood.

Ten years her senior, he was struck by her energy and enthusiasm.

“I found her very refreshing, she brought new perspectives. Of course, she was a little less mature in those days,” says Wong, who has worked with Chow on a host of projects since. “She has always been good at listening, bringing together people with different perspectives and being realistic in finding a solution. Her heart hasn’t changed.”

In 1985, Wong was organising a fundraiser for a research facility at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital and needed two MCs – a Chinese speaker and an English speaker. He chose Chow and a recently divorced 35-yearold rising star of the city council.

Layton would later tell people it was love at first sight. Chow recalls in her memoir that it took him just four nanoseconds to fall in love with her.

“Some of us never meet the one person on the planet best suited as partner and soulmate. I was lucky enough to meet mine. Before then, I had lousy luck with men,” Chow writes.

The first boyfriend she lived with, at the age of 17, suffered from a lack of ambition. The ones that followed were far worse. There was the former marine with a black belt in karate who, she says, came close to killing her twice. She was with him a year before she stopped making excuses for him and wised up to the fact that he wasn’t going to change. The next boyfriend seemed gentle but, when she ended the relationship, he hit her.

Chow had been a crisis counsellor after graduating from college so she was familiar with the pattern of abusive behaviour and had known that children who had witnessed violence could be prone to slipping into such relationships. So why did she fall for those men?

“I don’t know, you fall in love with some people and then you think, ‘Heck, why did I do that?’” she says.

An old-school romantic, Layton serenaded her, sent flowers and, significantly, won over her mother. When he and Chow married, in 1988, their wedding gift to each other was a tandem bicycle, a fitting present for a pair who worked so well together.

“I’ve never seen a couple who are so in tune with each other,” says Tong. “They finished each other’s sentences. They knew what the other person was thinking. They totally supported each other.”

Wong agrees: “It’s very rare to find a couple who work so well together; they never argued.”

Chow took the role of “playful aunt” when Layton’s children stayed over at the weekend. In her memoir, she writes, “Since Jack already had two wonderful children, and I wanted to focus on my public life, there was no need for us to have another child.”

In the year they met, Chow won her first election, and served as a school-board trustee for six years. In 1991, she became the first female Asian Toronto city councillor and served for 14 years before she was elected to parliament, in 2006.

Layton’s career was also on a rapid upward trajectory. From the city council, where he occasionally served as deputy mayor, in 2003 he became leader of the New Democratic Party (NDP). In May 2011, he led the NDP to its biggest ever victory, winning 103 seats and becoming leader of Canada’s largest official opposition in 31 years.

Three months later Layton was dead. He had been battling prostate cancer but soon after the election, doctors discovered an even more virulent cancer, the details of which have never been made public.

Given his high profile, Chow’s grieving was a public affair.

For most of her political life she’s had her husband by her side, so does she feel lonely without him?

“No, because I have my cats, my Mum, my team. I wish Jack was here but I never regret anything I have no control over,” says Chow.

“After Jack died I believe she became even stronger, she is more confident in herself now,” says Wong, who is one of three fundraising co-chairs on Chow’s campaign.

Soon after her husband’s death, Chow went on holiday with her best friend. Tong remembers discussing her plans for the future. “She said that part of what Jack was doing was making politics relevant to young people and she wanted to continue to engage young people in politics, which meant a lot of mentoring. I said, ‘That’s so much work.’ But she said it was what she enjoyed doing. She has so much energy.”

Chow’s day starts at 6am.

“I get up and go for a swim or a run, sometimes yoga if the weather is bad. Then I read the news – I get it all online now – and watch the news on TV. And then usually have a meeting at 8am,” says Chow.

She says she forgave her father 20 years ago.

“I was never really angry with him. It’s this question of when a person is mentally ill, how much responsibility do they bear when they do something wrong or is it an excuse? I’m not a psychiatrist so I can’t tell,” says Chow.

“Last year, when I was an MP, I had one of my staff visit all the new immigrant centres and ask, ‘If there was one service you would want expanded, what would it be?’ And they said their No 1 priority would be more mental health care for immigrants.”

Chow is a “doer”, good at getting people together, finding a solution. But that passion can take its toll. Tong says that when she speaks to her friend she reminds her to look after herself.

In the past 18 months Chow has had pneumonia and Ramsay Hunt syndrome, a virus that causes a temporary disorder of the nerves affecting the face, similar to Bell’s palsy.

“I said to her, ‘Are you taking good care of yourself?’ And she said, ‘I don’t get sick until I go on holiday, so I’m going to keep working,’” says Tong. “She’s a workaholic.”

Tong says she rarely talks politics with Chow but knows her friend well enough to realise that “she wants to carry on Jack’s legacy. She’s not doing it for money or power – she doesn’t get gratification from that”.

Last month, Ford branded Chow an irresponsible socialist and slammed her tax and spending policies. Doubtless, he’s just warming up and there will be a lot more mud-slinging before the election, but Chow says she’s ready for it.

“It’s not my first campaign. And when you know what’s important you can ignore the petty attacks,” she says.

So what’s her edge over Ford?

“I’m smarter, more disciplined, have the experience, care more and I’m not addicted,” says Chow.

That sounds like someone who has bounced back all the stronger from life’s knocks and is ready to fight a tough election.

Original Link: SCMP

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/192-SCMP-Olivia-Chow-1.pdf]

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/192-SCMP-Olivia-Chow-2.pdf]

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/192-SCMP-Olivia-Chow-3.pdf]

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/192-SCMP-Olivia-Chow-4.pdf]

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/192-SCMP-Olivia-Chow-5.pdf]