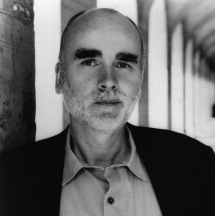

Polish poet Adam Zagajewski

— March 23, 2014Adam Zagajewski’s exile-tinged poems strike a chord on the mainland

Polish poet Adam Zagajewski will see the first two volumes of his poems translated into Chinese launched in Guangzhou this month, but he’s already made a name for himself among the mainland’s literati.

“I find my presence in China intriguing because it happened behind my back – and I say that without any sadness but rather with pleasure,” says Zagajewski, who was nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature in 2010.

A few years ago, Zagajewski heard rumours that Chinese poets had translated some of his poems and they were circulating on the internet. And then came an even bigger surprise: in November he won the Zhongkun International Poetry Prize.

Considered China’s literary Nobel, the Zhongkun is awarded every two years in Beijing with two winners in each edition – a Chinese and a foreign poet – and is the only literary distinction of its kind to be awarded to foreigners.

Academic commitments – Zagajewski teaches at the University of Chicago – meant he couldn’t pick up the prize in person, but he didn’t have to wait long for a second chance to collect a Chinese prize: on Wednesday he will be awarded the prestigious Poetry and People Award, a lifetime achievement honour, in Guangzhou.

Zagajewski, who reads classical as well as contemporary Chinese poets in translation, isn’t sure what it is about his poems that appeals to mainland readers. He says he only knows his poems from the inside, but he suspects it may be a connection between images and ideas. “It seems my poems are written images and images are translatable and underneath these images there are some ideas, some reflections,” he says.

This will be Zagajewski’s first visit to the mainland – and Hong Kong, where he will read from his work at the Fringe Club in Central on Tuesday – and he admits to being a little apprehensive about what to expect in a large Asian city.

For a man who has written so extensively about cities – specific cities, such as the one he was born in, Lvov, as well as generic cities – that may seem surprising, but he says he’s a European guy and middle-sized European cities are his ideal. Those that are not so small they are provincial, but big enough to have culture, such as Krakow, where he lives with his French wife.

His poetic musings on cities are wrapped up with the nomadic existence he lived for many years in exile, and even from his very early days. Born in Lvov in western Ukraine in 1945, his family was expelled by the Ukrainians to central Poland the next year.

“I was born under the sign of shifting borders. [Recent] events in Ukraine make me shiver because it’s like the past coming back, the possibility of changing borders once again, and we need as human beings some stability in our lives. This aggressive Russian policy is really scary – it brings back the worst European years,” says Zagajewski.

In one of his best known poems, To Go to Lvov, he writes of having to flee the city: “I won’t see you anymore, so much death/awaits you, why must every city/become Jerusalem and every man a Jew/and now in a hurry just pack”. But despite the obvious terror of having to abandon the city, the shifting borders, it ends on a positive note: “go breathless, go to Lvov, after all/it exists, quiet and pure as/a peach. It is everywhere.”

This delving into deep issues yet while maintaining optimism in the apparent darkness is typical of Zagajewski’s writing. At a reading recently, he was asked whether poets were always melancholy, dwelling on sadness, and was fast to quash the idea.

“Poetry is a strange mix of sadness and joy. There is some melancholy, but the very act of writing a poem liberates some joy. For me the ideal poetry is a poem that is neither sad nor joyful but has a kind of equilibrium between the two,” he says.

But it is Zagajewski’s life in exile that is one of the biggest markers on his work. He studied psychology and philosophy at university, and soon after graduating, while working as a young academic, he made a name for himself as a poet of the Generation ’68, referred to as the Krakow New Wave, challenging the government.

In 1975 his works were banned and in 1982 he moved to Paris, beginning 20 years in exile.

“I’m a good exile person, I know how to do it. I have my books, my writings, my music – there are so many things we can carry with us wherever we go. But I think I’ve done my share of exile and being back in Krakow is a huge joy,” he says.

These days, when he’s not teaching, giving readings or accepting awards, the 68-year-old is slowly finishing a new collection of poems. It picks up on many of the themes that have pervaded his work – time, history, silence, dreams and death – but there is a new sequence about the death of his mother.

“It’s just something slightly new, but I think the author is the last person to see the newness – I leave it to the critics to tell me what are the themes,” he says.

Original Link: SCMP