Documentary on the Maryknoll nuns

— March 11, 2014Documentary maker Nancy Tong talks to Kate Whitehead about her latest film and how it is prompting a new slant to her work

It’s 1922 and a group of young nuns arrive in Hong Kong transferred from their steamer to shore by sampan. The old archival footage is scratched, lending authenticity to this historical record and the sound of a lone harmonica gives the scene a melancholic feel.

That this visual record of the six Maryknoll Sisters arriving in the city exists is thanks to the savvy of the nuns themselves, but few beyond the sisterhood would ever have seen it if not for documentary filmmaker Nancy Tong.

Trailblazers in Habits, her most recent work and a radical departure from her previous work, is a portrait of the American nuns and what they achieved around the world. For Tong the story was intimately woven into the fabric of her own life too.

There are personal touchstones throughout that are markers of her life and memories. Take that lone harmonica playing as the six nuns, dressed in their grey habits, arrive. That sound has a special meaning for Tong. Growing up in Mong Kok in the 1950s, she recalls Hong Kong as a place with plenty of refugees and widespread poverty.

“I remember after the Shek Kip Mei fire there were all these people sleeping on our street. There was one blind man and he played the harmonica and it was the saddest thing in the world [because of] the emotion he put in it,” she says.

It took a little convincing to persuade Thomas Wagner, the composer behind the film’s score, that a harmonica would work. Blues films and Westerns were the place for harmonicas, he said, but she told him the story of the blind harmonica player and he was won over. The lingering, mournful notes fit the scene perfectly.

Tong made a name for herself with a string of hard-hitting documentaries. She was the creative force behind In the Name of the Emperor, a seminal work on the Nanjing massacre, and collaborated on Cancer: From Evolution to Revolution and Who Killed Vincent Chin?, about how an engineer was murdered and his killer went free. The Maryknoll film is in a whole new category.

Tong made a name for herself with a string of hard-hitting documentaries. She was the creative force behind In the Name of the Emperor, a seminal work on the Nanjing massacre, and collaborated on Cancer: From Evolution to Revolution and Who Killed Vincent Chin?, about how an engineer was murdered and his killer went free. The Maryknoll film is in a whole new category.

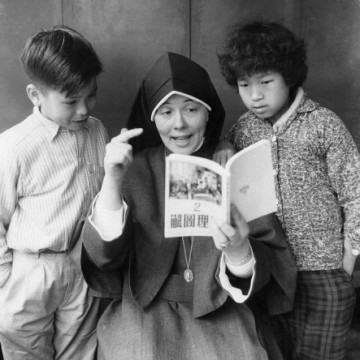

A still from Tong’s documentary Trailblazers in Habits, a portrait of a group of American nuns who arrived in Hong Kong in 1922. Photos: The Maryknoll Mission Archives “When I finished this film I realised it was a departure from my other work because my other films are all about war, diseases, dying and crimes and this one is about the human spirit. It’s an inspirational story,” she says.

And it’s a personal one, too. Tong knows the Maryknoll Sisters well. If not for them her life may have turned out very differently. She credits her mother with having the nous to queue overnight outside the school for an application form and then dress her in her best dress, a little bow in her hair, and tell her what to say to the sisters. Her admission represented not just the opportunity to learn English and for a good education, but to acquire the values that would shape her life.

In 1912, the Maryknoll Sisters were the first group of Catholic nuns in the United States to found an overseas mission. When six sisters arrived in Hong Kong 10 years later, they had few resources at their disposal aside from their faith, determination to succeed and brains – what comes across clearly through the documentary is that these women, who travelled all over the world, were very well educated.

Schooled by the sisters through the 1960s, it’s perhaps no surprise that one of Tong’s fondest memories is the annual school trip to the cinema. They saw My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music and other Hollywood favourites, and one year Sister Rose took them to see a Chinese opera. At a time when Hong Kong was a segregated society, Tong was impressed by the move.

“Sister Rose was crossing over to make us proud of our heritage and make us realise that we have this Chinese tradition of opera and singing,” she says.

The cinema became a huge part of her life. She tutored at the weekend to earn extra money and spent it all at the movies – Hollywood, French, Japanese films, she devoured them all, but was especially struck by Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon.

“It got me thinking about the possibilities of telling stories in film and what is reality. It totally opened up a whole new world for me,” she says.

But even though she couldn’t imagine her life without the cinema, she never considered studying film. She didn’t even think it was possible. Instead she went to the University of Wisconsin and studied fine art, specialising in photorealism.

And two years later when her family immigrated to Toronto she moved too and proudly showed off her straight-A portfolio to a professor at the University of Toronto, but they wouldn’t have her – photorealism wasn’t on the agenda. Disappointed, she was at a bus stop wondering what to do when she spotted an advertisement across the road.

“It was for the School of Film and TV. I didn’t even know there was such a thing,” says Tong.

Starting film school in 1975, one of just three women on the course, she realised she wasn’t at all politicised, something she puts down to the Hong Kong education system.

“At school we studied Chinese history, but never the revolution or modern Chinese history because which version would you study or teach? The curriculum was designed in such a way so that we weren’t analytical about society or history,” she says.

That soon changed. She began her career in Hong Kong working as a news reporter with TVB. The first project she worked on was a documentary about addicts trying to quit heroin and her subject matter has been hard-hitting ever since, mainly dealing with social issues with a focus on the experience of Chinese-Americans. She moved to New York in 1981 and found work as an independent film producer.

She’s a little nostalgic for her early days in the industry when film producers were given more time to work on documentaries, more time to research and find the story they wanted to tell. She’s fortunate that since 1999 teaching positions have paid the bills, leaving her free to pick and chose her film projects with no pressure. After eight years at City University, in 2009 she accepted a position as visiting associate professor at the University of Hong Kong, where she teaches for half the year.

Dividing her time between Hong Kong and New York, where she has a home, provides a good balance and she’s already casting about for her next project. She hasn’t settled on a subject yet, but knows that after Trailblazers she’s no longer content to look at one isolated incident, instead wanting to look at the human experience and consider spiritual issues around it.

“In the Maryknoll film there is a very universal theme in all their experiences, to look beyond yourself as how one relates to the rest of the world whether it is joy or suffering – even if you suffer, don’t take the joy away,” she says.

This new, perhaps more philosophical, bent to her work took her a little by surprise, but she’s enjoying it and says it could be something to do with a recent significant birthday.

“I’ve just turned 60. I’m trying to find some reason for all these things – why do we live, why do we die, why do all these horrible things happen?” she says.

But the fact that this milestone was celebrated on the Galapagos Islands, kayaking, swimming with dolphins and giant turtles and camping on the beach suggests that she’s got absolutely no plans to slow down. She casts about her office, trying to find the words to explain her new cinematic approach, to try to transcend the day-to-day of our human existence and recall the core values.

“I always find language limiting in expressing these things. In films you have that accumulation of images and sounds and scenes where you can bring it forth,” she says.

That magic moment, the amassing of images, sounds and scenes comes towards the end of Trailblazers in Habits when there is a poignant shot of one of the nuns, Sister Rose, looking at a 90-year-old Chinese woman.

“You see the sisters relationship with the Chinese and their relationship with the Japanese all through and then it is captured in that one frame, one moment, when she looks with so much feeling and compassion at this other person,” says Tong.

Original Link: SCMP