Colour schemes

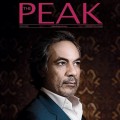

— May 1, 2014It’s a Sunday night, and as The Peak’s creative team sets up props, background and lighting for a cover photo shoot, Adrian Cheng is firmly in the director’s seat – just where he wants to be.

![]()

Unlike other high- powered interviewees the team has worked with, Cheng has a clear idea of what approach to this month’s shoot will work for his artistic sensibilities. Given his background, work and passions in life, this comes as no surprise.

Cheng, scion of the world’s largest jewellery business and a leading Asian property conglomerate, shares two important lessons he says he learned from his grandfather and father. “They taught me to be really be humble and to make more friends because you never know, the person sitting next to you may be the next president of the United States.”

And the second lesson? Have a vision and stick with it. It’s safe to say the 34 year-old Cheng – one of the world’s youngest billionaires – has taken these pieces of guidance to heart.

His grandfather Cheng Yu-tung came from humble beginnings, starting out as a young salesman in a jewellery store in Macau. It’s a classic rags-to-riches tale – he impressed the storeowner, married his daughter and went on to found the jeweller Chow Tai Fook and real estate empire New World Development. Just before the outbreak of World War II, when he was starting out, the world was a very different place, but his wisdom is still sound.

“The world is changing, there is no formula you can apply to every single venture or business, but there are some basic rules – like sticking with a vision,” says the Harvard-educated Cheng who worked at Goldman Sachs and UBS before joining the family business.

It takes courage to carry through your vision, even if you come from a moneyed family. Cheng’s vision was a new breed of shopping malls – one that set out to marry art, nature and people – and an arts foundation.

“You look at the shopping malls in Hong Kong and China, everything is the same, the same layout, the same brands, the same box. There is no personality and the customers are changing too – they are getting more sophisticated and they are getting bored,” says Cheng.

Just 28 when he launched the first hip K11 Art Mall in Hong Kong in 2009, he describes it as “museum retail”. The arty formula proved a winner – it was profitable after a year and soon after that the sales doubled. He opened another in Shanghai last year, and there is more in the pipeline.

For the ongoing Claude Monet exhibition at the K11 Art Mall in Shanghai, Cheng collaborated with the Musee Marmottan Monet in Paris to bring 55 pieces to the city. On day one, 60,000 tickets were sold and they had to put a temporary hold on the booking system.

“It proves that everyone is thirsty to look at good art and especially masterpieces and those who have had a big influence on the contemporary art landscape,” says Cheng.

And it’s a shrewd business model. At the K11 art malls, people don’t need to queue up to see a big exhibition, such as the Monet one; they get a ticket and are called when it’s their turn to enter. In the meantime, they can wander around the mall.

“It’s a win-win for the museum and the retail space,” says Cheng.

But he insists that it’s not just about the draw of a great master painter and the lure of big brand appeal. Of course, people come to see the “Water lilies” and “Wisteria”, but alongside the exhibition are symposiums where he hopes to encourage debate and dialogue. Which brings him to the project perhaps closet to his heart – the K11 Foundation, which he founded in 2010.

It’s the first charitable foundation in China to offer a creative platform to artists – at home and overseas – and aims to change the landscape of contemporary Chinese art. Artist-in- residence programmes at the K11 Art Villages in Wuhan and Guiyang operate as incubators for young and emerging Chinese artists.

There have been important lessons along the way, not only about trusting himself and his vision, but also about how to get an effective team on board.

“A hybrid model is so new, so when you are hiring people you have to educate them, train them and create the vision that you want. A lot of the time it is really about motivating people – and that’s challenging. I’ve learned a lot about that, how to deal with people, how to motivate them,” says Cheng, who encourages his management team to read a book every month.

He’s made great strides in a relatively short time and there are no signs of slowing. Two more K11 malls are scheduled to open on the mainland in 2015 – in Beijing and Shenyang – and there are another 19 K11 projects in China targeted for the next five years. Cheng is clearly a man not afraid of change. “I like steady change – it ignites reinvention and stimulates you to improve,” she says.

So if he doesn’t fear change, what does he fear? It’s the only question that seems to stump him. He pauses and when he speaks after a moment’s reflection his answer sounds genuine, perhaps even a personal revelation.

“It may sound strange, but sometimes I’m afraid that I’m not being productive. I’m not a workaholic, but I feel very uneasy when I’m not producing things, wasting your time,” he says.

He’s been that way since he was young, driven by an urge to create, to be productive. After his wedding in 2009, it was work that drove him back to the office, putting his honeymoon on hold.

“If you want me to go crazy just put me in a big house and say there is no plan or schedule, just loiter around the house, watch some TV. I have to always be in the process of creating and thinking and implementing and changing things – whether it’s a product or a charity, I just need to see an impact,” says Cheng.

The creative urge and artistic flair has bubbled close to the surface all his life. Trained as a classical tenor in high school, he used to sing opera and musicals and even sang two songs at his own wedding, one in English and one in China, but never considered turning professional.

“I thought [singing] was my talent, but being a talent and using your talent for your livelihood or profession is different – I just knew it was only my talent and wouldn’t be my future job,” he says.

What he has succeeded in weaving into his work life is his creative eye as a designer and has created a couple of jewellery collections for Chow Tai Fook. Last year’s collection of 15 pieces, “Ombre di Milano” (Shadows of Milan), was well received and sold well at auction. In March he launched “Reflections of Siem”, a collection inspired by Cambodia, which will be auctioned to VIP customers in October.

It took him two months to design the Cambodian collection, doing the sketches by hand. Craftsmen then spent 18 months working on each piece, meticulously setting diamonds and using delicate stone setting techniques. The knockout piece is “Remembrance”, a stunning 27.65-carat oval red tourmaline with diamond-studded gold branches inspired by the winding roots of Cambodia’s old banyan trees.

“This year we’re focusing on discovery, eclecticism and ethnicity – so the collection represents that total heritage. And it’s also about spirituality,” says Cheng, who had the photo shoot for the collection in Cambodia, the models posing with the jewellery amid the crumbling ruins of the Angkor Wat temples.

It’s a good time to be celebrating heritage. This year marks the 85th anniversary of Chow Tai Fook. And the spirituality is implicit in the fine craftsmanship and simplicity of the pieces; the delicate design of some inspired by Cambodia’s floating villages.

“Spirituality for this generation is a common theme. With globalisation, a lot of information, the web age, this generation is searching for simplicity, you want to be grounded, searching for a sense of spirituality whether it be through religion, meditation, self-reflection or your own search,” says Cheng, who is Catholic.

That quest, which he sees as a constant of his generation, is reflected in everything he makes: “Whether it’s the jewellery or K11 or even my real estate apartment or the retail malls or the art foundation – everything is going back creativity and spirituality.”

Don’t be fooled by the seemingly soft talk of expression and creativity – while he’s all for trusting your gut feeling and spontaneity, he makes sure all his business moves are grounded in solid research.

The actual name “K11” was totally random – “I saw the letter K on a piece of paper” – but its foundation is solid.

“You need to do a lot of research. When we launched the K11 Foundation and the K11 shopping malls, we did a lot of research on the problems, the art landscape and what the customer wants and hates, what can be improved – and we are looking at a five to 10-year horizon,” he says.

With 2,000 Chow Tai Fook jewellery stores on the mainland, he and his team rely on a complex IT system to stay on track of store sales and product sales. About 80 percent of sales are in second, third and fourth tier cities and customer tastes vary from place to place.

“Different regions and cities have their own tastes – they eat different foods, have different cultures, speak different dialects. I think establishing a good team management, implementing a system through IT and doing a lot of customer feedback, a lot of touch points and big data analysis,” says Cheng.

Chow Tai Fook counts 1.1 million VIP customers on the mainland and another 100,000 in Hong Kong. And increasingly they are looking for more affordable pieces. Hong Kong customers have deeper pockets than those on the mainland, with the typical VIP spending HK$40,000 on the first purchase and HK$12,000- $13,000 on the second.

“Hong Kong is a bit more sophisticated because of the economy. In China people are trying to find out more about the product and they are willing to experiment,” he says.

The single stud diamonds and classic gold pieces still make up the bulk of sales, but he has noticed a demand for more unique pieces, special designs perhaps inlaid with tourmaline or semi- precious stones.

The chain’s reach is vast, with jewellery for everyone from newborn babies and professional women, to classic lines for a more conservative market. Collaborations have proved successful. They teamed up with Disney to produce solid gold Winnie the Poohs and Superman pieces, both popular on the mass market. Launched at the end of April was a collaboration with St Martins in London for more avant garde pieces aimed at young customers who want something a little more daring.

“I call myself a cultural or creative entrepreneur or family entrepreneur, to create new venture(s) within an established business,” says Cheng.

His two favourite words are “renew” and “reinvent”. For a business to succeed it needs to keep evolving, he says. But for all his bold talk about change and reinvention, there is a part of Cheng that is a traditionalist, holding family ties close. He hasn’t forgotten those words of wisdom about reaching out and making friends.

“I’m lucky that I became a trustee of the Royal Academy of Arts and part of the Tate Modern and the Pompidou and I’m on the committee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” says Cheng. If his grand vision is to change the landscape of contemporary Chinese art, he’s certainly cultivating the right friends.

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/185-Peak-Adrian-Cheng1.pdf]