Keeping it simple

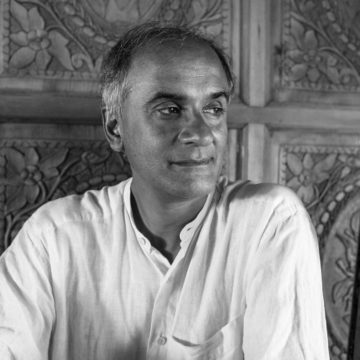

— September 7, 2019- ‘I grew up in Britain, but I’m entirely Asian’ he says, explaining his affinity with Hong Kong and Singapore

Novelist and non-fiction writer Pico Iyer has always had a soft spot for Hong Kong. His first visit, in 1983, was as a 26-year-old reporter for Time magazine and he’s been a regular ever since. He has twice featured in the Hong Kong International Literary Festival – in 2003 and 2006 – and will be the headline author at this year’s event, in November.“Whenever I come to Hong Kong, I feel I am walking into the future of the planet – there is such a sense of dynamism. And also, a little bit of my past because of the British monuments and the British people that are so much part of what I remember from my boyhood,” Iyer says over the phone from the Raffles Hotel in Singapore, where he is the property’s first official writer in residence.

His time in Singapore, staying with his Japanese wife, Hiroko Takeuchi, in the newly renovated heritage property, has been a chance to reflect on his connection with the Lion City, which led to the publication in July of This Could Be Home: Raffles Hotel and the City of Tomorrow.

“I grew up in Britain, but I’m entirely Asian. As soon as I came to Singapore I felt that [the city] is my brother, this is a place with a strong British presence and grounding, but distinctly Asian. Of course, I feel that even more with Hong Kong,” says Iyer.

But don’t assume that his yearning for the Britain of his youth means he wants to write about it.

“I sometimes think, the only place I can’t write about is England because I have the illusion that I know England and so my eyes are closed to [it]. I somehow assume how the days will go and it has the feel of yesterday’s breakfast,” says Iyer.

What keeps his creative flame alive is the sense of otherness or foreignness, of being an outsider looking in.

Born in Oxford to parents from India, Iyer and his family moved to California when he was seven, a shift he describes as one of the biggest displacements of his life. After a couple of years “living on a dirt road which ended up in the mountains, perfect John Wayne country”, the canny kid persuaded his parents that, given the exchange rate, it would be cheaper to send him to school in Britain than to the local school in Santa Barbara. So, that’s what they did, first to Eton and then to Oxford University.

During his “gap year” between school and university, he travelled by bus from Santa Barbara down to La Paz, Bolivia, and then to Brazil and up the east coast of South America, through the Caribbean to Miami. By the end of that journey, he’d caught the travel bug. While at graduate school, at Harvard University, he spent the summer holidays writing for the Let’s Go series of guidebooks.

If “liberation” sounds a curious choice of word to describe breaking away from a privileged education, consider that he’d spent eight years, from the age of 17 to 25, studying nothing but literature. This has made him more self-conscious as a writer, he says, and the intensity of focus has shrunk his view.

“Part of me is envious of friends who are writers and can draw on history or social science or anthropology or mathematics, and have their hands on this whole body of knowledge that is interesting and exotic. I don’t have that. I stopped studying literature because I realised the more I studied it, the more I was losing my ability to write,” says Iyer.

The antidote to all that literature was his four years at Time magazine. His office was on the 25th floor of the Rockefeller Centre, in New York City, four blocks from Times Square. It was a dream job for an aspiring writer. If academia had stifled his writing, working for a news magazine undid the damage.

“Time magazine was amazingly good training in learning how to try to write concisely and clearly, writing more for communication than self-expression,” says Iyer.

And it was Time that sent him on his first business trip – to Hong Kong. This turned out to be a life-changing journey. Not the Hong Kong part, but what happened on his return. The flight called for an overnight layover in Japan. With time to kill before his departure in the morning, he took a shuttle bus into Narita. The bus stopped at a Buddhist temple and he was transfixed. By the time he got on the plane to New York he was determined to live in Japan.

It took three years to extricate himself from his job. He must have done it graciously because when he told his bosses at Time that he was going to Japan to write in a monastery, they offered him a monthly retainer, so long as he wrote occasional stories for them.

The plan to live in a Kyoto monastery for a year and write about the experience lasted all of one week – “it was too similar to the English boarding school”. Fortunately, the arrangement with Time lasted 14 years. He moved out of the monastery and into a small single room.

“No toilet, no telephone, no visible bed. So, the part of me that was drawn to a simple life was genuine, it was just that the monastery wasn’t the place for me then,” says Iyer.

The monastery would, however, become a recurring theme in his life. But before we get to that there’s a love story. During his third week in Japan, he visited a temple in southern Kyoto where a Zen master was being initiated. There he met a young mother of two. They made conversation as far as possible – “with my limited Japanese and her limited English” – and discovered they were the same age and were both fans of Bruce Springsteen and Audrey Hepburn. She invited him to her daughter’s fifth birthday party five days later and the rest, as they say, is history.

“My monastic year, for which I was contracted to write this book, turned into this very different year of watching this woman who had barely been out of Kyoto and never been on a plane, completely transform her life as dramatically as Japan changed its life at the end of World War II,” says Iyer.

A year after they met, Hiroko walked out on her marriage, taking her two children. During that year, Iyer wrote the book he says he gets asked about most often, The Lady and the Monk (1991), about his year in Kyoto – the “lady” being Hiroko and he being the “monk”. The romance is subtly told and the reader doesn’t learn about Hiroko’s divorce – “a very brave and rare thing to do in 1988”.

For the past 27 years, Iyer and his wife have lived in the same small, two-room rented flat in a suburb of Nara, the ancient capital. Iyer would be content spending all his time writing here, with occasional trips to see his elderly mother in Santa Barbara, but work means he’s on the road a lot. With three books coming out this year, he has essentially been travelling for eight months.

“My longing is to sit still, and the reality is quite the other. In the first nine months of this year I’ll have taken 58 flights. And this year I’ll stay in at least 38 hotels,” he says.

When TED Talks began its publishing arm in 2014, a savvy editor asked him to write a book about going nowhere, The Art of Stillness. Considering his attraction to monasteries and the fact he spends part of each year in a Benedictine hermitage in California, it’s surprising to hear that Iyer doesn’t meditate. That said, his wife thinks all those hours spent in silence at his desk are a form of meditation.Iyer will talk about stillness at the Hong Kong Literary Festival. He will also be speaking about Japan because his new books include Japan: Autumn Light: Season of Fire and Farewells – “I spent 16 years trying to distil my whole life in Japan into a thin, haiku-like book” – and its companion piece, A Beginner’s Guide to Japan: Observations and Provocations.

This year’s festival, which runs from November 1 to 10, will feature 41 international authors and 24 local authors. Other writers to look out for include British novelist John Lanchester, Irish writer John Boyne, Australian writer Markus Zusak and Canadian artist Renee Nault, who adapted Margaret Atwood’s 1985 classic The Handmaid’s Tale into a graphic novel.

Original Link: Post Magazine