Wisdom of the ages

— July 28, 2019Next-level yoga: the secrets of Tibetan yoga explained, from tantric sex to redirecting dreams

- Forget your downward facing dog, Ian Baker’s book goes deep – explaining how yoga can change the course of a dream, and transfer consciousness as you die

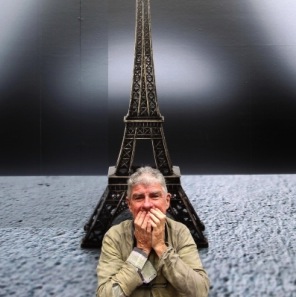

Could you spend a month alone in a cave? That was the challenge put to Ian Baker.

The American first visited Nepal as a 19-year-old undergraduate in 1977, fascinated with the mountains, Buddhist art and meditation. After completing a masters in literature and anthropology at Oxford University, he moved to Nepal to work for the School for International Training in Kathmandu – and to learn about yogic practices outside monasteries.

“I went looking for a teacher. I wasn’t going to become a monk in this life, but I wanted to understand the essence of the practice. The teacher said, ‘Can you spend a month alone? Come back when you have a month free and spend it in a cave’,” says Baker.

He did just that. In his early 20s, he went deep into the Himalayas and spent a month alone. Happy with his commitment, the teacher, Chatral Sangye Dorje, took him on as a student.

“It was a very personal immersion, which led to experiences, which led to an academic interest. The non-monastic yogic tradition fascinated me – that done in caves and forests, often in solitary retreat or with a partner,” says Baker, whose latest book, Tibetan Yoga: Principles and Practices, was published in June.

In the Tibetan language, the word yoga, or naljor, means to know yourself in the deepest way possible, and Tibetan Yoga: Principles and Practices offers a rare insight into this. This isn’t yoga of the downward facing dog variety. This is the next level.

This is about ultimately freeing yourself from disempowering struggle and discontent and awakening empathy. This is deep.

It’s also a rare glimpse into a world that has traditionally been kept secret in Tibet – many of the teachings have never been written down, instead passed down orally from teacher to student. As Bhakha Tulka Pema Rigdzin Rinpoche explains in the book’s foreword, not because knowing one’s true nature could ever be considered harmful, but because Buddhist practices that integrate all aspects of life on the spiritual path can easily be misunderstood.

“As much as the book has a scholarly approach, it’s an outgrowth of personal experience and experimentation, and that’s the key of yoga. We experiment with ourselves, we turn our bodies and minds into a laboratory,” says Baker, speaking on the phone from London, where he is preparing for a 2023 exhibition on Tantric Buddhism at the V&A museum.

It took a while to set up an interview with Baker. His publicist was vague about his whereabouts – “he’s travelling, somewhere remote” – and, when pushed, suggested “the Himalayas, maybe Bhutan”.

It turns out this is par for the course for Baker. He has spent decades living in Nepal and travelling in the eastern Himalayas and Tibet and has written seven books on Himalayan and Tibetan cultural history, environment, art, and medicine. The Dalai Lama’s Secret Temple (2012), which illuminates Tantric Buddhist meditation practices, was written in collaboration with the Dalai Lama.

“The very fact of writing a book like this is a break from tradition, it wouldn’t previously have been written for a general reader. But times change. His Holiness encouraged, his instruction was that ‘the time for secrecy has passed and more harm is done by not writing about it, or else traditions will die out’,” says Baker.

Tibetan yoga begins where the more familiar yoga ends. In fact, the asanas – the postures – help to prepare a person for meditation.

“All these physical movements of stretching the body help to open up the energetic centres – that’s what fascinated me. In Tibetan yoga, there’s a set of six processes, practices which can be undertaken at different stages of life. It’s about integration and synergy,” says Baker.

The six processes he refers to are: tummo, the cultivation of “fierce heat” (kundalini yoga in Hindu yoga); gyulu, “illusory body” yoga; Ōosel, the “clear light” awareness that encompasses waking and sleeping; milam, “dream yoga”; powa, the transference of consciousness from the physical body at the time of death; and bardo yoga, involving near-death and after-death experiences.

Tibetan Yoga isn’t a “how to” book or instruction manual, it’s a scholarly tome. But if you read it closely and have some experience of yoga and meditation, much is revealed. Thames and Hudson has a reputation for producing beautiful books and this is no exception – it’s beautifully illustrated with colour photographs of yogis, landscapes and Buddhist art.

So, let’s cut to the chase – for many, tantric yoga is associated with sex. The practice of karmamudra, or sexual union with a physical or visualised consort, is well depicted in Buddhist Tantric art. Saraha, the most celebrated of the mahasiddhas (a person who, by the practice of meditative disciplines, has attained siddha or miraculous powers), proclaimed of the erotic experience, “In this state of highest bliss, there is neither self nor other.”

Baker explains that the yoga of intimate relationships can be teased out to show a more evolved way of relating to those who are closest to us, free from the negative fallout of emotional attachment. He talks about visualising your partner as a deity – and transforming desire into a state of empathetic bliss.

“Both partners make the vow that, as these energies are aroused, not to succumb to damaging forms of attachment,” says Baker.

This isn’t about open relationships or transient sexual partnerships. He says the most profound unions are those in long-lasting, exclusive partnerships that recognise a deep sense of engagement and appreciation of the other without the negatives that can come with attachment.

“The idea with all these yogas is we don’t have to change our lives. We integrate into things that are happening during our lives – waking, sleeping, dreaming, dying,” says Baker.

Take Tibetan dream yoga (milam naljor), which is about recognising that what arises in a dream is illusory and therefore alterable. This process is about waking up within a dream, recognising it for what it is – if you’re flying or walking through walls, you know you’re likely dreaming – and bring an inquiring mind try to change the course of the dream.

“In this way, you can slice through the subconscious and find what’s at the heart of an experience, something you might not recognise in your daily life.

“On the superficial level, it’s recognising all our experiences – waking or dreaming – are dreamlike and not to become too attached them. It’s an opportunity to alter the course of our experience. By changing that reality, it has a follow-on effect in our waking state. That everyday experiences are a reflection of our everyday mind gives us a greater sense of awareness,” says Baker.

In a chapter titled “Exit Strategies”, Baker explores powa, the yoga of conscious transference at the moment of death. In this, one visualises oneself as a Tantric deity and, compressing one’s breath, uses the sound of the chosen deity’s mantra to open the “aperture of Brahma” between the frontal and parietal bones at the crown of one’s head.

If you can do this at the time of death, so the book explains, your consciousness will be ejected from the body and enter the transcendental Land of Bliss.

“This release of consciousness at the end of life – how to open up energetic channels within the spinal cord – is given very openly, often at mass congregations. Powa is the quickest way for people to recognise the energetic core of our consciousness,” says Baker.

He is working with a Bhutanese lama who is a master of the six-yoga system and plans to lead a group to Bhutan next year, from April 25 to May 5. If that sounds like something you might be interested in, keep an eye on his website ianbaker.com for more details.

Original Link: SCMP