David Thompson

— January 31, 2019The Sydney-born chef also reveals how he fell in love with ‘heady, delicious, exotic’ Bangkok, and recalls meeting his partner of 30 years, Tanongsak Yordwai, over tequila shots in a dive bar

The world’s worst cook I was born in Sydney in 1960. My mother was one of the world’s worst cooks. A lovely woman and smart, but she hated being a cook and that dislike showed. That I survived her cooking is a miracle. I finished a degree in English literature and my parents were absolutely horrified when I told them I wanted to go into a kitchen. At 22, all of a sudden, I became obsessed by food and compelled to read and eat as much as I could. I also worked in restaurants. I was an appalling cook and made so many mistakes – I was hopeless – and then it all started to come together.

Bangkok bound In 1986, I went to Bangkok on holiday. I loved the unpredictability, the irrationality of it; it was dangerous and unknowable to me. Add to that the charm and sweetness of the Thais and their food – I was enthralled. I was lucky, my parents had bought me a house when I turned 21 and I did the clever thing – I sold it and lived off that for a while. I look back and can understand why they weren’t happy I did that, but I used the money to learn. As it happens, it was an investment.

Many people find that when Thailand gets under your skin, it’s the most deliciously engaging and enticing of places. For me, it wasn’t just about the people and how pretty they are, it was the culture and, to a lesser extent, the food, because at that stage, I thought Thai food was green curry and fish cakes and all the clichés that still litter Thai restaurants around the world.

Tastes of Thailand I met Tanongsak (Yordwai, his partner) in a cheap bar in Bangkok drinking tequila shots – that was 30 years ago. He was a classical Thai dancer and came in with some friends. It was the night after my birthday, so I’ve never forgotten our anniversary.

Through Tanongsak I met an old woman who introduced me to a cuisine that is one of great depth and breadth of provenance, of fantastic ingredients, of cultural significance. I went to her house for six months and Tanongsak often translated for me. I’ve still got the book of notes I took when I was with her. It was my introduction to what I now know as Thai food. She was 90 and grumpy and an old dragon, but she was an heir to an ancient tradition of cooking. She had been brought up in an old palace. Those old palaces were like finishing schools for girls of a certain class who would go there to learn the finer points of finesse that women should have, according to Thai culture. I remember my surprise when she said she could smell whether a dish was too salty. Now I know what she meant. Thai food isn’t just about following recipes, it’s about chasing tastes.

Success in Sydney I went to school in Thailand to learn the Thai language and I started to read and collect old recipe books. They, along with eating and tasting and meeting people, became the basis on which I learned my craft. I not only stayed in Thailand for two years but had money left over to open a restaurant in Sydney, the Darley Street Thai, in Newtown (in 1991). When we moved the restaurant to Kings Cross, that’s when things started to kick off. It was one of the first beautifully designed restaurants I had, and one of the first that had a proper architect designing it rather than a restaurateur fitting it out. Then we opened Sailors Thai in Sydney in 1995.

London calling I moved to London in 2001 and started working with (Singaporean) hotelier Christina Ong, who owns the COMO chain. We opened Nahm in her Belgravia hotel (The Halkin). It was around the time of Cool Britannia. I loved it so much I became British – my grand parents were British, so it was easy. I did think I’d stay there for quite some time. Then in 2010, we moved Nahm to Bangkok.

There had been changes to European Union regulations that decimated our supply of ingredients. It became difficult for me to operate a restaurant in London because we lost 90 per cent of our Thai ingredients and it hurt. You could get alternatives but they were grown in India or Burma and had a different taste.With the zeal of a convert, I like to keep to orthodoxy rather than explore the green and merry fields of culinary innovation. By opening in Bangkok, we were able to obtain these wonderful ingredients and Nahm took root. I decided then and there I’d never do another Nahm outside Bangkok.

Streets ahead In 2015, the first Long Chim was born, in Perth, Australia. It’s a Thai street-food restaurant and we have branches in Sydney, Melbourne, Singapore and Seoul. Having street-food restaurants was predicated on making sure I would never suffer the privations I did at Nahm in London. Street food by its very nature is half Chinese, it’s hybridised, and I can always get rice noodles and Chinese greens because they’re available everywhere.

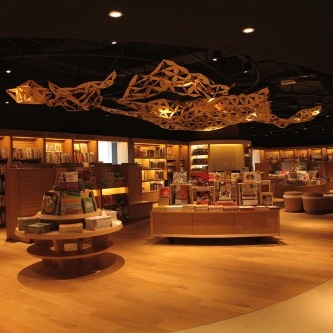

Aaharn – our new restaurant in Tai Kwun – is a different kettle of fish. We altered the concept to fit the site; it’s too upmarket for street food. Downstairs we’ll have snacks to go with the drinks, but upstairs is more refined. It’s proper Thai food as I understand it. I decided instead of having a large menu as we did at Nahm, here, we’d have about 15 to 20 items that I would change often.

Balancing act Tanongsak and I got married in Britain in 2003. We live in Bangkok and have a condo in Sathorn. We’ve managed to get that work-life balance thing done perfectly – I work, he lives.

I still find the same timeless joy in cooking that I had when I started. Few people can say they still have the same excitement and satisfaction in doing what they did when they started their career. It’s one of the joys of being a cook because it’s rejuvenating. The value I obtain is personal and internal and not derived from other people or monetary success; it’s about the sheer pleasure of executing something well. I’m very lucky.

Original Link: Post Magazine