Followed by pro-Beijing newspaper

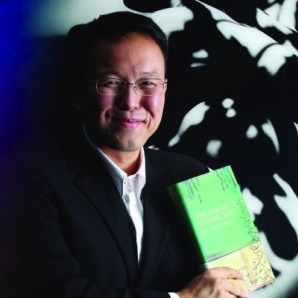

— December 20, 2018The Australia-based American academic Kevin Carrico, who has researched tensions between Hong Kong and mainland China, as well as the city’s independence movement, speculates why tabloid Wen Wei Po might be interested in his movements

![]()

Small-town life I was born in 1980 in Cambridge, Maryland, in the United States. It’s a small town, the sort of place where everyone knows everyone. My dad is an accountant and my mom was in social work. I have two younger sisters. In junior school, I studied French and then Latin – I enjoyed studying languages.

When I was 15, I left to go to boarding school in Pennsylvania. Life in a small town was quite boring and I was excited to get out, even if I was just exchanging one small town for another. When the time came to go to college I thought it would be interesting to try learning a challenging language and Chinese seemed the most challenging option.

Bright lights, big cities In the spring of 1998, I joined a Chinese educational tourist trip to Beijing, Shanghai, Suzhou and Hangzhou. As well as the cultural experience of new food, new people, new ideas and a new language, it was exciting to spend time in real mega-cities.

For study, I went to Bard College, outside New York City. My degree was in Asian Studies; it combined training in Mandarin and the study of ancient history, modern history and classes on contemporary issues. It was a four-year degree and during that time I studied in Qingdao, Harbin and Nanjing – three fairly different cities and quite distinct from anything I’d experienced before.

Chinese lessons After college I went to the Hopkins-Nanjing Centre for Chinese and American Studies, a joint graduate programme run by Johns Hopkins University and Nanjing University. American students take all their classes in Chinese and the Chinese take their classes in English. I had built up the basic language skills I needed during four years of undergraduate studies, and the Hopkins-Nanjing Centre gave me the opportunity to move beyond studying the language to using it and immersing myself in it.

Under quarantine In 2003, my studies in Nanjing coincided with the arrival of Sars and the Hopkins-Nanjing Centre closed a month before we were due to finish. Most people on the programme went back to the US, but I decided to stay. It was a time of intense paranoia in Nanjing and anyone who was an “outsider” was thought to be potentially carrying Sars. When my neighbours saw me moving into my new apartment, they reported me to the police.

I was placed under quarantine even though I had no symptoms. CCTV portrayed quarantine as a fun experience – you get to sit home, relax and people bring you food. In reality, quarantine was nothing like that. No one brought me anything and if I tried to step outside an old lady from the neighbourhood would yell at me to go back in. Twice a day two guys came in biohazard suits to take my temperature. After about five days I was declared Sars-free.

Article 23 A few months later, I came to Hong Kong for the first time, to get a China visa. I’ve always been interested in politics and, coming from China to Hong Kong, I immediately felt a sense of relaxation. This was a society that had Chinese cultural roots, but whose approach to political discussion and whose culture seemed completely different.

I arrived in the midst of the Article 23 controversy – people were openly debating Article 23 (which relates to national security), they were politically involved and had a sense of humour about politics and enjoyed speaking critically about it. It was such a contrast from the society I’d spent the past year in. Almost immediately I fell in love with the city and its mature, open, frank approach to political issues. Since that first visit in 2003 I’ve visited Hong Kong on average once a year.

Lost in translation After I got my China visa, I went to Shanghai where I worked until 2007 for a translation agency. We translated whatever we were given. Sometimes it was interesting like a public relations press release and other times you’d get a washing machine instruction manual.

The breaking point for me was when I was asked to translate a video game. I decided to do something more intriguing with my language skills, so I applied to PhD programmes in anthropology. I went back to the US and pursued a PhD in socio-cultural anthropology at Cornell University. It was in New York that I met the Chinese-American woman who would become my wife.

Localism and independence My PhD research focused on a group known as the Han Clothing Movement. It mixes fashion with nostalgia and ethnic relations and ethnic tension; it was a fascinating project looking at China at a moment of rising nationalism and conservatism. My dissertation, The Great Han: Race, Nationalism and Tradition in China Today, was published in 2017.

In 2016, I landed a job at Macquarie University, in Sydney, where I teach Chinese history, contemporary Chinese society and both ancient history and modern history. Part of my job is conducting research. At the moment I’m researching tensions between Hong Kong and (mainland China) and the various cultural manifestations that are emerging from these tensions, including localism and the independence movement, which is clearly why (newspaper) Wen Wei Po wanted to follow me on my recent visit.

Citygate surveillance I don’t know how Wen Wei Po knew I was coming to Hong Kong. I arrived on December 7, but it was only the next day that I realised I was being followed. I’d decided to go to Tung Chung. As an anthropologist I do fieldwork to experience things. I didn’t have anything scheduled, I thought I’d just walk around and see the crowds I’d been hearing about there since the new bridge opened.

On the train I noticed a lady in a University of Oxford sweatshirt sitting a block of seats away from me. I felt she was looking at me. As I walked around Citygate mall I began to realise this lady was everywhere I went. I took the escalator into the central area of the mall and as she rode up I tried to take a picture of her, but she turned and rode the escalator backwards. That was when I realised this wasn’t just a coincidence. Clearly, I was being followed by someone who wasn’t the sharpest tool in the box.

Agents of the PRC? I went to the cable car to see if she’d follow – and she did. When I tried again to take a photo of her she hid behind a tree. I thought, “I’m going to go back to my hotel to relax.” I didn’t see her again. Only rarely in the week that followed did I have a feeling I was being followed.

On December 11, I felt I was being followed, but they were better trained and disappeared once I’d spotted them. I didn’t know who was doing it. Was it PRC agents? Was it one of the Beijing newspapers? Of course, it’s a thin line between PRC agents and newspapers like Wen Wei Po. So it was a relief when the Wen Wei Poarticle came out and I knew who had been following me. It was also disconcerting in so far as they had captured me at moments I wasn’t aware of – the weirdest picture was one of me at the airport, I had no idea someone followed me all the way to the airport to get a picture of me in a line at departures.

Outside the law I’ve done a lot of things that probably p***ed off Beijing. I’ve been outspoken about Tibet and, over the past year, Xinjiang. I do research on tensions between Hong Kong and China and the evolution of the idea of Hong Kong independence. So, there are reasons people at Wen Wei Po, who work for the Liaison Office, would be interested in me. I don’t think it merits stalking, but I suppose they have different priorities. It’s a way of saying, “We’re watching you.”

Everything I’ve done in Hong Kong is perfectly legal. I do doubt the legality of some of the things Wen Wei Po has done because I had meetings that were scheduled privately over Facebook messenger that were photographed. Either they had access to my phone or they had a pathetic person camped out in my hotel lobby 24 hours a day.

Disappearing freedoms I was followed last year. On June 30, I’d spoken at the banned National Party Hong Kong Rally at Baptist University. I spoke there because I felt that in a city that has freedom of speech, particular topics can’t be banned and that includes the discussion of independence.

The next day, as I walked around the July 1 festivities and protests, I noticed a guy obviously following and photographing me. In January, I’m moving to Monash University (in Melbourne), where I’ll be a senior lecturer in Chinese studies. I plan to come to Hong Kong again in the near future, I’m not intimidated. I hope the Immigration Department isn’t intimidated by this into pulling a “Victor Mallet” on me. It’s a sign of the fragile and quickly disappearing idea of one country and two systems.

Original Link: SCMP