Chien-Chi Chang talks about the slow process of joining the elite agency and how he came to shoot a marriage market in Vietnam and immigrants in New York’s Chinatown and their families back in Fujian

Fear of the frogmen I was born in 1961 and grew up in a very rural area in Taichung, Taiwan. The first colour I think of is green because of all the rice paddies. My father was a mechanic and a farmer and my mother was a housewife. I had four sisters, all younger than me.

Looking back, it was quite a difficult life. I didn’t realise it then and only later my mother told me that there were times when we had very little food. The whole community was made up of seven or eight families, all from the same ancestor, and everyone was suffering from lack of food. I went to a local school and didn’t study Mandarin until elementary school. My parents wanted me to do well and carry the family name, and I went to Soochow University (in Taipei) and studied English.

In 1984, after university, I did two years of compulsory military service. I was stationed at an outpost close to Xiamen – we were so close we could see China. Back then the situation was tense. It was pitch black at night and we were very afraid of falling asleep. We were told a story that sometimes the frogmen from China would swim across the water in the middle of the night and cut one of your ears off.

Something just clicked Taiwan was stifling. Martial law was still in place and you never knew who was watching or listening. It became like a Panopticon – you don’t know if you are being watched, but you assume you are and act accordingly.

After my military service I worked as a teaching assistant at Soochow University for six months and then went to the United States, first to Ohio State University and then I transferred to Indiana University, where I took a master’s in education. I am forever grateful to my professor, who suggested I take a photography course. That’s when I realised it was something I could do.

The second year of the programme was very independent and I was shooting the whole year. I had three jobs at the university – working at the school newspaper, for the school yearbook and for the school photography lab. Everything I did was about photography.

The Magnum effect My original idea had been to go back to Taiwan after my studies, but that changed. I won the College Photographer of the Year award and with that came an internship with National Geographic. I also got an internship with a newspaper in Oregon and an internship at The Seattle Times. So, I was doing three internships in one year. The Seattle Times offered me a job and then I worked at The Baltimore Sun.

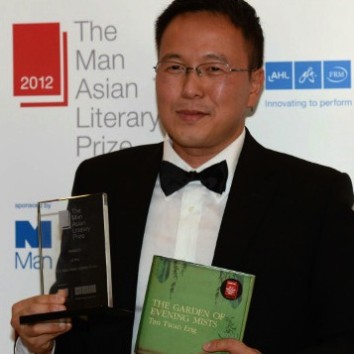

A number of Magnum photographers encouraged me to send in my work. I applied in 1995 and was nominated. Becoming a Magnum photographer is a slow process. In 2001, I was elected as a full member. There was only one other Asian photographer at the time.

Every time Magnum (a photo agency founded in 1947) takes on a new photographer it changes the chemistry of the whole organisation. There are a few photographers who are working on similar subjects or areas, but for the most part, when a new photographer is considered or accepted, he or she has to have a way of using photography as a language that is unique. There are 48 or 49 photographers at Magnum now. This year we took in four, but in the past, they only took in one or two. We have been looking for more diversity, so it’s not so much a white boys’ club.

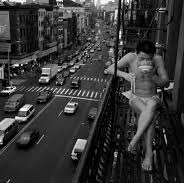

Connection and alienation I moved to New York and lived in Kew Gardens Hills (in Queens) – I was between two airports, JFK and LaGuardia. In 1992, I started a project photographing the lives of Chinese immigrants in New York’s Chinatown. The men lived in cramped, subdivided cubicles. When the guys told me about their families back home in Fujian their eyes would glow, so, in about 1996, I started tracing their stories, going to Fujian to photograph the families as well. One of the guys told me he was quite nervous about a single guy going to his home and meeting his wife and four children.

The project is still a work in progress. I’ve been following them for so long, I know the families really well and I feel the story is still growing, so I continue.

For me in my work there’s always this thing about connection and alienation, this push and pull. It probably comes from my personal experience, especially since after college I didn’t go home. I was cast out. I’ve always had this thing about tradition, commitment and the pressure to do certain things. I guess it’s always the visible chains versus the invisible chains. “The Chain” was a project I did in a mental asylum in Taiwan. Two people are tied together – a stable patient chained to a mentally unstable one.

A marriage market What is unique with Magnum is the freedom. From time to time assignments come and you can pick and choose. In 2003, I worked on a project called “Double Happiness”; it was a sad project, but I felt I needed to do it, it was my idea. I ended up going to Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam) six times to shoot the marriage market. Brokers on both sides would set it up and bring men from Taiwan to Ho Chi Minh City to buy wives. Most of the men were farmers, they were mainly 40-somethings and, in Taiwan, wouldn’t have been able to get a date. In Ho Chi Minh City, they had 70 or more women paraded in front of them. The girls were young. They always said they were above 18, but I wasn’t sure.

The first time I went I was just getting my feet wet, seeing how it worked. The second time I understood more. To complete the project, I realised I had to shoot similar pictures, but it wasn’t just repetition, it was adding another layer. I thought I was done after the fifth trip, but once I put the images together I realised there was one part that was lopsided, so I went back to shoot the men and women getting married.

Later, Koreans started coming to Ho Chi Minh for the bride market. After a number of exposés it was widely reported and the government began to put regulations in place.

Graz is not greener It was in New York that I met the mother of my children; she is also a photographer. She is Austrian and, in 2010, we moved to Austria. We live in the south in Graz; it’s quite a conservative place and quite racist.

We have two children – one is five and the other is almost six and a half. I speak to them in Mandarin. Taiwan is home, Austria is where my kids are. I miss New York; I go back two or three times a year and when I do, it feels like I never left.

Original Link: SCMP