Being Allan Zeman

— July 31, 2018Hong Kong-based entrepreneur and tycoon Allan Zeman FCPA isn’t shy and is quick to spot opportunity – and dress up as a jellyfish. But there is more to him than meets the eye.

![]()

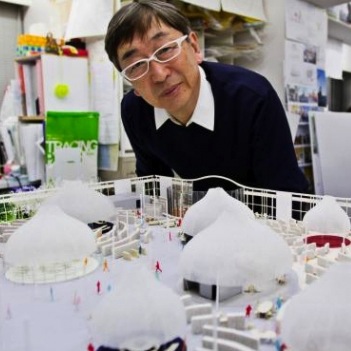

Allan Zeman FCPA is in a chipper mood. Fresh from a meeting with the local airport authority, the billionaire fondly known as Mr Lan Kwai Fong for pioneering Hong Kong’s best-known bar and restaurant district, is all smiles and sparkly eyes as he strides into his office. His trademark tailored suit and open-neck white shirt set off a deep tan and, for a man with plenty of balls in the air, he certainly looks relaxed.

His secretary has a stack of cheques for him to sign and diary events to schedule, providing me with an opportunity to take in the collection of photos and knick-knacks on his generously proportioned desk. There’s a red lacquered box marked Wynn Resorts – Zeman became non-executive chairman of Wynn Macau after the founder’s sudden departure in February – and a soft-drink bottle emblazoned with his name. Noticing my interest, he picks up a small figurine of himself.

“Some university students presented me with this, isn’t it fun?” he says of the plastic caricature.

Zeman is not a man to shy from publicity. Experience has taught him that being prepared to be the face of a brand pays off – he has dressed up as a jellyfish and gone swimming with dolphins to boost business. It’s this seeming lightheartedness – a willingness to have fun – combined with shrewd business acumen that has made him so well loved in Hong Kong.

“I’m not just about making money,” he declares. “I’m also about trying to give back to society [and] I enjoy doing that. I really enjoy being Allan Zeman – I walk down the street and people want to take pictures of me.”

Switching allegiances

He might be one of the most recognisable Western faces in Hong Kong, but he’s no longer a Westerner – at least according to his passport. Zeman renounced his Canadian passport in 2008 – at a time when many Hongkongers were just picking up theirs – and became a naturalised Chinese citizen with right of abode, which allows him to hold a home return permit when entering mainland China.

It was a smart move; a bold statement of his confidence in Hong Kong’s future. Put your money where your mouth is? Zeman has done more – he’s offered his whole identity.

“I’ve done so much for China and Hong Kong and I woke up one day and got tired of being called a gweilo [foreigner]. I haven’t been back to Canada for 15 years now. I thought – I really feel Chinese, this is my home. My kids grew up here. I wanted to become localised.”

Looking like a Westerner while holding a passport that states he’s Chinese does cause some double-takes at airports and border controls. Entering mainland China, he is often told he is in the incorrect queue and should be in the line for foreigners.

“When I give my passport to the immigration officer they usually think it’s a fake,” Zeman says.

There’s even more confusion at other border controls. When an immigration officer notes that he has declared Chinese [as his nationality] on his arrival card, he or she is usually thrown and says, “You are not Chinese”.

“Rather than explain I just say, ‘It’s a genetic problem’,” Zeman says. He can’t be serious. Does he really say that?

“All the time. They look at me like I’m crazy.”

Zeman is anything but crazy. At the age of 69, the entrepreneur is as sharp as ever and shows no signs of slowing. If there’s an off switch, or even a dimmer switch, he has no plans to use it. Born and raised in Montreal, Canada, his father died when he was seven years old, leaving him and his mother with nothing.

“In Montreal and Quebec at the time, if you didn’t have a will – and my father didn’t – the government took your money,” Zeman says.

“It was a crazy law. We worked to survive. It made me very independent and very mature for my age.”

At the age of 10, Zeman had a morning newspaper round before school. By the time he was 12, he landed a second job cleaning tables at a restaurant, which meant lying about his age and saying he was 16. Between the two jobs, he was pulling in US$60 a week, double what his school teachers were earning. He saved the money and bought a car at 16.

“I was the only kid in high school with a car. It was a convertible and the girls loved me. I was always very entrepreneurial.”

While his classmates brought packed lunches to school, Zeman went to a restaurant, often treating friends. He left school at 16 and got a job at a lingerie company – “because it sounded attractive to a 16-year-old”. Working in the stockroom, he quickly realised the money was in sales, so at 17 decided to become a salesman. He put on a suit and tie and applied for a job at Canada’s largest dress-making company.

“I knew nothing about ladies’ dresses. I said I was 22 and had all the requirements and experience wanted in the ad – there were no computers, so they couldn’t check. I took a chance. They asked me what my salary was. I was earning US$60 a week at the time, [but] as a salesman I figured US$200. I got the job.”

After a couple of years selling female fashion, he decided to set up his own business. Imports seemed the thing to do, so aged 19 he started a company called Jump for Charlie, importing women’s sweaters from Hong Kong. The fact that he’d never run a business before didn’t faze him.

“I’ve always felt if someone else can do something, why can’t I? I always had that inner strength and confidence in myself. I guess because I experienced the bad side of life at a young age, with my father dying, it makes you stronger and matures you.”

Buying into Hong Kong

He came to Hong Kong on product-buying missions and worked hard, and by the end of the first year he’d made US$1 million. It was then that he learned a big lesson. His accountant explained that he’d have to pay 50 per cent tax and, on top of that, he’d be stung by corporate tax as well, whittling his US$1 million to US$425,000. Soon after that he was in Hong Kong on another buying mission and discovered that the tax rate was just 15 per cent.

“I said, I may as well move to Hong Kong, make money, then move back to Canada,” he recalls.

He moved to Hong Kong in 1975 and fell in love with the energy of the city and its can-do spirit. There was a sense that anything was possible.

“In Canada, my business was with Canadians. In Hong Kong, my business was with the world, and I was going from strength to strength.”

In order to expand, he kept opening offices until he had “about 30 offices” around the world, from Bangladesh to South Korea, Egypt and South America. With friend and business partner Bruce Rockowitz, he grew Colby Group to become the second largest trading firm in Hong Kong. In 2000, they sold it to competitor Li & Fung for HK$2.2 billion in cash and stock.

When he was running his trading firm, Zeman often entertained designers and buyers, and became frustrated by the limited number of restaurant options. Most quality restaurants were in hotels and the atmosphere was formal, with men required to wear shirt and tie.

“Coming from the fashion industry, we didn’t wear socks and those of us who had long hair weren’t used to that,” Zeman says.

In Hong Kong, build it and they will come

Scouting about for a location, Zeman found Lan Kwai Fong, an area occupied by linen and embroidered tablecloth warehouses, and just a block from the main thoroughfare Queen’s Road Central. Where others saw grubby old tenement blocks, Zeman saw potential charm.

“I look at things not for what they are, [but] for what they could be. I look at the positive. I thought if we can get people to walk here, then we are in business.” In 1983, he opened California Bar, a hip restaurant that turned into a buzzy club later in the evening.

“Michelle Yeoh was [one of my] customers along with Jackie Chan, Faye Wong, and Danny Chan. They were just kids who wanted to make it and some had already done okay. It was glamorous, a place to see and be seen.”

He saw great promise in the area and in 1988 made a bold move by buying the building and renaming it California Entertainment Building. Gradually, he began moving tenants out of the podium level and lower floors and putting in restaurants. The idea for restaurants on upper floors came from a trip to Tokyo, another vertical city with famously high rents. The strategy had an unexpected bonus.

“What I didn’t realise was that rentals for commercial were three times the price of offices for the same space, so I was buying the building based on office rental and increasing the value of the building by putting in commercial tenants. The banks said, ‘Whatever you’re doing, keep doing it’.”

In 1992, he bought the building next to it, California Tower, then gradually snapped up more property in Lan Kwai Fong.

“I started buying up more property in the area – no one really knew what I was doing – and reconverting the area. We ‘pedestrianised’ the area and people would come and stand outside and have a drink. It became very popular.”

A brand-new theme

In 2003, the then chief executive Tung Chee-hwa – likely impressed with Zeman’s success with Lan Kwai Fong – called and asked if he’d consider becoming chairman of Ocean Park, a struggling theme park on the south side of Hong Kong Island. Zeman thought Tung’s request was “crazy”, but on the sixth call decided to give Tung face and take a look at the park.

“When I first went there, the paint was peeling and they were losing money. I thought with a little TLC we could give it a facelift. Staff uniforms looked like they were from the 1950s. Coming from the fashion industry, those details were important to me,” Zeman says.

Despite knowing nothing about theme parks, he took the job and quickly set about building a strong management team around him, changing the staff uniforms and upgrading the facilities and restaurants. Noticing that Chinese visitors love jellyfish, he opened a Halloween-themed jellyfish attraction and dressed up as a jellyfish for a press conference to announce the new attraction. The press lapped up the stunt and Zeman made the front page of newspapers not just in Hong Kong, but around the world.

“We didn’t have a lot of money and I realised this was a way of getting free advertising. Every time there was an event I dressed up in different costumes. The public loved it, the press loved it. Actually, I hated it, but it was a way to promote what was coming up in a novel way.”

It comes as a surprise to learn he didn’t enjoy the dressing up, because he made it look like he was having a ball, and he did make a very good calypso dancer, but it comes back to Zeman’s shrewd business sense. After all, this is a man who founded Asia’s best-known bar and nightlife area and yet is a teetotaller.

In 2011, Lan Kwai Fong Chengdu officially opened, and he says there are more projects in the pipeline in China – in Shenzhen, Shanghai and the Greater Bay Area, which he is especially buoyant about.

Zeman has a relationship with Beijing and he also has close ties with Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam, who he backed during her election campaign and continues to support as one of her council of advisers on innovation and strategic development.

Evolution theory

Zeman is big on innovation and admits that although Hong Kong showed early technological promise with the 1997 release of the Octopus card – a rechargeable and contactless smart card – it has since become complacent and, instead, China has stormed ahead.

“Today Shenzhen is ahead of Silicon Valley, it’s leading the world,” says Zeman, who sits on the board of the Alibaba Entrepreneurs Fund.

Regularly approached by young entrepreneurs, what he looks for is a confident founder with a strong team and a product that is different, saleable and scalable. Basic business principles still apply – he wants to know how long it will take to turn a profit.

“I always look at things through customers’ eyes, never at things through being a boss. Will this sell? Why is it different? I usually challenge a young entrepreneur with questions. I don’t always look at the upside, I look at the downside. If I can cover the downside of the business I might say okay, this has a chance.”

Metta, a new platform designed to bring entrepreneurs and the start-up community closer together, is typical of the projects that appeal to Zeman. It’s tech, it’s entrepreneurial. He saw a spark and invested, giving the group a space in his revamped California Tower when it reopened in 2016. Another recent investment was in the Hong Kong-based ophthalmic services provider, C-MER Eye Care, which went public in January and saw shares soar more than fourfold within a week of listing.

“It’s incredible the way technology is changing illness. This is a very good sector, especially in China,” Zeman says.

Zeman is a Hong Kong icon and his future is intimately woven into the future of his adopted homeland. He might be approaching 70, but has the energy of a much younger man, which is likely in part thanks to his wholesome lifestyle – eating healthily, spending 80 minutes in the gym every day – no exceptions – and leading a balanced life. His downtime is on Sundays, which are reserved for family and usually spent boating.

“It’s not how much money [you make], it’s really about having a good life, being a good person and [achieving] fulfillment – that’s the most important thing and what makes me go, so I don’t really think about retirement. I still feel very young and am surrounded by young people.”

The Hong Kong of tomorrow

The future for Hong Kong, says Zeman, is the Greater Bay Area, which will link the two special administrative regions, Hong Kong and Macau, with nine mainland cities within a two-hour radius of Hong Kong; namely Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Foshan, Huizhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Jiangmen, and Zhaoqing. This will be supported by new infrastructure – a high-speed rail link and the Hong Kong Zhuhai-Macau Bridge.

“The infrastructure will totally change the Greater Bay Area,” Zeman maintains.

“I’m very optimistic that this is the future of Hong Kong. If we just continue the way we are going, we will be marginalised because [mainland] China is moving really quickly.”

Original Link: INTHEBLACK