Not THAT Gordon Chang

— September 3, 2016Being mixed up with China sceptic is ‘the bane of my life’, says Gordon H. Chang, recently in Hong Kong, who sees America as both fearful of and attracted to China but unlikely to be eclipsed by the rising power any time soon

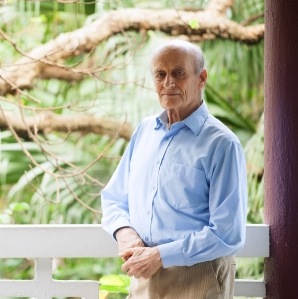

Gordon H. Chang, professor of history at Stanford University, is at pains to explain that he is not Gordon G. Chang. Yes, both men write about China, but that’s where the similarities end.

Gordon Guthrie Chang, a lawyer, author and television pundit, is best known for the sensational 2001 book The Coming Collapse of China, in which he predicted the country’s imminent downfall. History proved him to be way off the mark, but he is still forecasting doomsday scenarios for China.

On the other side of the China debate is Gordon Hsiao-shu Chang, offering a far more measured and well reasoned account.

His take on China is so far opposed to the other Chang that it’s hard to believe people ever mix them up, but it happens regularly. For almost 20 years, the Stanford professor has redirected calls intended for his controversial namesake.

“I have to clarify this because it’s become the bane of my life. People confuse us all the time – we get e-mails for one another,” Chang told a packed audience at the Asia Society in Admiralty last month. “One day I got a long-distance call from someone who sounded like Miss Moneypenny [the fictional secretary in the James Bond world] who said she was calling from MI6 or an intelligence service, and said, ‘We hope you will come and join our generals and admirals for a roundtable discussion about the coming collapse of China.’”

He joked that he briefly toyed with accepting the all-expenses paid trip before putting Miss Moneypenny straight, just as he is keen to put the Asia Society audience straight.

The society’s Miller Theatre, once an ammunition store, is filled with the society’s usual post-work crowd – business folk, academics, China watchers, the savvy and the curious. They are beginning to warm to the “other” Chang, and he tells them of his close connection to Hong Kong: he was born in the then British colony.

The next morning, in the Tiffin Lounge at the Grand Hyatt Hong Kong, where he is staying, Chang explains how he came to be born in the city. He could have easily been born in America – where his Chinese-American mother and Chinese father met – or China, where they married. But fate had something else in mind. His father was working in Nanking when his mother, carrying their first child, began experiencing problems with the pregnancy. The couple came to Hong Kong in search of good medical care.

“She had me in St Teresa’s Hospital and the doctor was a Scot, Dr Gordon, and so to honour him I got named Gordon. Not many Chinese in my day were named Gordon,” he says. (Aside, of course, from the other Gordon Chang, who had a Chinese father and a Scottish mother.)

Chang, 68, has lived in the US since he was nine months old and identifies as American, although like many people today it’s not a hard and fast line. He grew up speaking English, but his home life was both American and Chinese. His father was an artist and was sent to America shortly before the bombing of Pearl Harbour by the Chinese government as a cultural ambassador.

“He came to the United States to promote US-China friendship and used his art and interest in Chinese culture to befriend Americans. Because of him I grew up with art, Chinese culture, and we’d go to museums to look at Chinese art. And from him I also inherited an interest in international and cultural relations,” Chang says.

It’s only now, as a respected and tenured academic with the luxury of time to reflect and write, that he is able to appreciate how the various strands of his life have played out in his career and writing.

“As you get older in life you find out in many cases that we are who we are meant to be, there’s a sort of destiny,” he says.

It’s interesting that he uses the word “destiny”, because he’d wanted it in the title of his most recent book, Fateful Ties: A History of America’s Preoccupation with China, but the publisher, Harvard University Press, ruled it out.

The book, published last year, takes a historical perspective of US-China relations. When he was first approached by Harvard University Press six years ago to write on China, he surveyed the current literature – of which there is a lot – and determined that there was no real historical perspective on the US preoccupation with China.

“The United States has a particular and peculiar obsession with China, it’s a current that runs throughout American history,” Chang says.

What he argues in the book is that Americans have looked towards Asia for the future of their country from the very beginning.

“They thought about the Pacific, Far East and China. The future of the country lay in that part of the world, not old Europe from which they came,” he says.

He takes the story back to 1492 and Christopher Columbus’ discovery of America, pointing out that the Italian was actually trying to get to Asia, and that by taking the Western route he accidentally stumbled on America.

Chang’s own interest in China, which was piqued by his father, continued at college and, after earning a BA from Princeton University and a PhD from Stanford University, he deepened his research into the history of US-East Asian relations and Asian-American history.

In his early career he focused on high-level decision-making, looking at the triangular relationship between the US, China and the Soviet Union, but in recent years he has become more interested in the softer, fuzzier side of international relations – the cultural side.

“I wanted to be able to explain how formal decisions were made, and there you have to go into thinking about the attitudes, the values, the experiences, the world view.”

Eisenhower, he says, referring to the US president who ordered the country’s military to support Taiwan, “didn’t exist in a vacuum – he has a history as a person and in society”.

For the Asia Society audience, he skips through several hundred years of history, pointing out America’s dual attraction to and fear of China – it’s a dynamic that has remained, from an interest in Chinese ceramics and the lure of the massive China market, to cold war fears of China invading America, the “Yellow Peril”, and current tensions in the South China Sea. The big difference today is that China is an immense power.

“Paradoxically, the two countries are more linked and integrated than ever in history – economic, political, military, tourist, trade, culture, education, intellectual engagement – despite the fact that there is so much tension in China,” he says.

He finds it “curious” that if Americans had been asked in the 1950s what they wished China would be like in the future, they would likely have hoped for a big, market-oriented country. And yet here China is today – a monster market-oriented country – and the two are at loggerheads.

Despite the talk of the decline of American power, Chang doesn’t see the US being eclipsed by China any time soon – certainly not in his lifetime. He cites the advantages of American English (“the language of the world, international intercourse, is no longer British English, it’s American English”), military power (“the US military budget is equivalent to the rest of the world’s put together”) and soft power (“movies, cultural values, sports, leisure activities, fashion”) as the key drivers keeping America ahead in the power stakes. And then there’s the tricky issue of China learning how to operate on a world stage.

“I think they understand they have a lot to learn about how to operate as a global, political leader commensurate to its economic power. Even though they want to be a global leader they don’t know how to think about it in those terms yet,” he says.

He doesn’t shy away from talking about the current situation, seeing US relations with China as tense on all levels – political, military and social. And he’s concerned that American public opinion and Chinese public opinion towards each other is so negative, having plunged dramatically in the past seven years. But where he’s most comfortable commenting is on the lessons learned from history, and he’s got his fingers crossed for a long-term view.

“Yes, there are specific issues – the South China Sea, copyright issues, human rights – but we are all going to be around for a long time so you’ve got to figure out a way to get along. You can’t let the emotions and intensity of the moment obscure the long-term possibilities, opportunities, advantages that both sides have. For the foreseeable future the two will have to find ways to not just co-exist but to mutually prosper.”

Original Link: SCMP