Connectography

— July 1, 2016Parag Khanna, the well-travelled author of new book Connectography, can change the way you see the world, writes Kate Whitehead

YOU HAVE TO BE on the ball to keep up with Parag Khanna. The global strategist speaks fast and enthusiastically, bouncing from one idea to the next at lightning speed. Within minutes we’ve gone from banned books to growing up in Dubai and the global connectivity revolution. It is one long fluid conversation, the 38-year-old finding connections at every turn.

Khanna isn’t your average academic. His look is more Silicon Valley corporate cool (jeans, crisp white shirt and a jacket) than fusty professor. And sure, he’s got letters after his name and a PhD in international relations from the London School of Economics (LSE), but his take on the world has come as much from a life lived and travelled as from libraries.

His background is well suited to his international-relations role – he was born in India, raised in Dubai and the United States, lived in Germany, where he passed his Abitur (final secondary school exams), and took degrees at Washington’s Georgetown University and LSE. He now lives with his wife, Ayesha, and their two children in Singapore.

We are in a snug corner of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club, in Hong Kong’s Central district, and by the time our coffee arrives – 15 minutes into the conversation – we’ve already circumnavigated the globe a couple of times and my head is beginning to spin. Academics often speak slowly and deliberately, choosing their words carefully, but not Khanna. It’s as though the sentences are queued up in his head and he can’t get them out fast enough.

The original draft of his latest book, Connectography: Mapping the Future of Global Civilisation, ran to 240,000 words before publisher Random House carved off a big chunk about the types of government that are best equipped to cope with today’s world. He joined forces with Random House in 2004, after pitching an idea for a book about empires and how they influence the world order. The publisher gave him three years to travel and research the subject.

The original draft of his latest book, Connectography: Mapping the Future of Global Civilisation, ran to 240,000 words before publisher Random House carved off a big chunk about the types of government that are best equipped to cope with today’s world. He joined forces with Random House in 2004, after pitching an idea for a book about empires and how they influence the world order. The publisher gave him three years to travel and research the subject.

“I was young and single then; it was an amazing adventure,” Khanna says. “I backpacked all around the world, on buses and trains.”

He travelled through Russia, North Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and elsewhere, trying to discover how the world’s three competing superpowers – the United States, Europe and China – extended their influence through trade networks and how their different styles of diplomacy fared in emerging markets. The resulting book, The Second World, was published in 2008.

His next, How to Run the World (2011), looked at global chaos and envisioned a new world order, but it’s his latest, which Khanna refers to as the completion of his trilogy, that should really make his name.

Connectivity is the buzzword du jour: we all want to be connected, we value connectivity. (Well, everyone except the British, apparently, who have voted to break their connection with the European Union.) Khanna has been fortunate in releasing the book bang on trend – the English edition came out in April, the Chinese edition in June – but he insists it wasn’t timed to hit a publishing sweet spot. It has been 20 years in the making.

“It all started with my first undergraduate course in geopolitical theory, in 1996. This entire trilogy is a response to a single class I took in my sophomore year in college,” Khanna says. “Geopolitics is the relationship between power and space.

In this latest book he looks at how connectivity and geography will affect the future of global affairs. He lays out his central argument in the first few pages: “We are moving into an era where cities will matter more than states and supply chains will be a more important source of power than militaries – whose main purpose will be to protect supply chains rather than borders. Competitive connectivity is the arms race of the 21st century.”

The case for cities being of greater value than states runs through the book. He posits the question: are there any great countries that do not contain a great city? Answer: no. It’s impossible to imagine a stable state without a stable city. Metropolises are the foundation of society.

Listening to Khanna speak for any length of time is to be struck by a series of “aha” moments. His impressive memory and broad understanding of the global economy mean he can pluck any number of examples from across history and the planet to back up sweeping statements.

I ask for an elevator pitch in an attempt to get him to pin down his vision and he comes up with this: “The winners and losers in the 21st century are decided by democracy versus authoritarian, rich versus poor. It’s old versus new, and those countries that have the newest stuff are the winners – that’s basically what I’m arguing.”

And we know where the new stuff is happening: “Asia may borrow ideas, technology, capital and investment from the West – they do it all the time – but they are the ones implementing it,” he says.

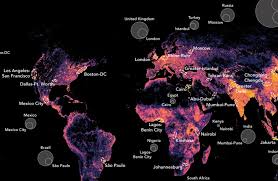

The best way to get an understanding of Khanna’s view of the world is to look at his maps. There are 38 colour maps in the book, in two inserts, and they are an absolute joy. To grasp their value, first consider that most charts of the world are shaped by physical geography (rivers, mountains, seas and so forth) and by political geography (countries, states). But not Khanna’s.

“This is a book of maps of functional geography. It’s how we use the world. None of [the commonly available] maps show us how we use the world, they show us how we divide the world,” he says. “This is a first for any book – to map global functional geography.”

He designed the maps, coming up with the concepts and sourcing the data, and then contracted the University of Wisconsin Madison Cartography Lab to create them. They have proved such a hit that the publisher has produced poster-sized versions. The one getting a lot of attention in the US, and which now hangs in Facebook’s Californian offices, is “United City-States of America”, which divides the country into imagined economic regions.

“This is what America should look like. Notice that I omit the 48 states – they are an added layer of bureaucracy that America doesn’t actually need. They are only useful if you are running for president and trying to get delegates, it doesn’t help you run as an economy,” Khanna says.

He explains that because every member of Congress represents a particular district within a state, they don’t fight for state-wide investment.

“And the governors actually want cross-state investments, but they have no power [in Congress], so there is a lot of very perverse politics in play. The situation is irredeemably unfixable from what I can tell. I vote with my feet,” he says, of his decision as a US citizen to live outside the country.

Facing the US city-states map is one of China, a juxtaposition designed to make a point: China is organising itself into an empire of megacities with networks along the coast and America is not.

“China is consciously moving in this functional direction whereas America is still wedded to a political map that was created in the early 19th century and it refuses to evolve. China is evolving despite thousands of years of provincial histories – it’s evolving functionally,” he says.

“China is consciously moving in this functional direction whereas America is still wedded to a political map that was created in the early 19th century and it refuses to evolve. China is evolving despite thousands of years of provincial histories – it’s evolving functionally,” he says.

A map of the Pearl River includes the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau bridge, which is still being built, and shows how the delta is becoming one integrated economic corridor covering a dozen cities.

“Despite the political differences in the status between Hong Kong, Macau, Zhuhai and Shenzhen, they are infrastructurally becoming more interconnected. People treat [the Pearl River Delta] as a megacity of 45 to 50 million people whose population is expected to rise to 70 million,” Khanna says.

Only by understanding global connectivity can you understand the economic value of a place, he says.

Khanna is clearly pleased with his maps, so I’m not surprised when he flicks through the book to that showing the world’s megacities and says, deadpan, “This is the most accurate map of global civilisation that has ever been made. Every single human being in the world is on this map.”

Khanna predicts that by 2030, 70 per cent of the world’s population will live in cities. But he also points out that cities of less than 1 million people fail – just one of his many factoids – and his explanation runs into a story of megacity clusters and of service economies that struggle when the scale isn’t there. Simply put, when there aren’t enough people buying cups of coffee and clothes to support such businesses, service economies falter.

“In American cities of less than 1 million, people are going bankrupt,” he says.

He compares Detroit (population: 700,000), which has yet to recover from the financial crisis, with Dongguan (population: 7 million), a manufacturing centre that suffered significant setbacks in the financial crisis with many jobs lost and facilities closed, but where the population has fared better.

“In Detroit, there are no high-speed rail networks and they are certainly not subsidised. Chinese can get on a train and move cheaply. If the government says, ‘Go to Inner Mongolia, there are jobs and cheap housing there,’ people will get on a train and go. In America, if they say, ‘Detroit is finished, you’ll never get a job, move to Phoenix,’ people can’t afford the Greyhound bus ticket and it will take months to get there and they don’t know anyone,” Khanna says.

This willingness and ability to move to find work and maintain a good wage is what Khanna calls “resorting”. He says it has happened all over China because it’s a country of megacities, but in the US it’s happened only in New York and Los Angeles, the nation’s two largest cities.

“America is very antiquated, people are very tied to where they are,” he says.

Of course, connectivity isn’t 100 per cent perfect, but Khanna warns we shouldn’t be too quick to blame the process for some of the world’s biggest ills, such as terrorism, pandemics, cyber wars and unwanted immigration.

Take the world’s top five criminal syndicates. They are thriving because they are able to conduct global operations, leveraging connectivity on the black market. Is that the fault of globalisation? No, says Khanna.

“Globalisation is a neutral thing – people use it and leverage it as they can.”

As for the threat of global pandemics, he says we’re getting much better at isolating health scares. Over the past several years the world has faced ebola and bird-flu threats and people have been quick to react, fearing a repeat of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which infected an estimated 500 million people worldwide. In every case, the story soon disappeared from the news. As much as connectivity may open the door to such risks, it’s also often the solution, the conduit through which quarantine measures and treatments can be rushed in.

Connectography is broad and wide ranging and we have touched on just a few issues (he addresses others in a Ted Talk available online). But before he charges back out into the heat of Lower Albert Road to further promote his book, I ask him where he sees himself living in the future

He approaches the question with the focus and sincerity he has applied to all my questions. “I can only imagine conducting my present lifestyle out of a great hub,” he says, somewhat predictably. He rules out Los Angeles and New York: “been there and done that”. Dubai has its merits: “centrally located and superconnected but hot for half the year”. London gets a mention: “fabulous”. But while he doesn’t commit to a firm answer, he hints very strongly at Singapore.

“There is something about Singapore – it’s like the capital of Asia – and Asia is where 5 billion people are, so if you want to understand and be in contact with the future of human civilisation, you want to keep in close proximity to Asia.”

Original Link: SCMP