From Berkeley hippy to Dalai Lama’s personal physician

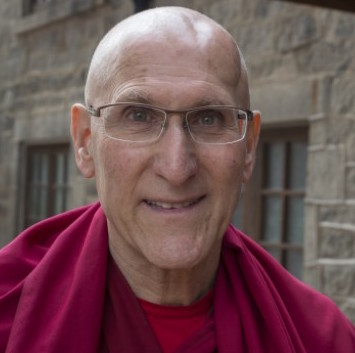

— May 15, 2016The American doctor and Buddhist monk, a visiting professor at the University of Hong Kong, tells Kate Whitehead about losing his wife, finding faith and how he came to be personal physician to the Dalai Lama

AT DEATH’S DOOR I grew up in southern California and, in summer, the days were long and after dinner we all used to go out, a bunch of kids in the neighbourhood, and play sports on the street. I have a younger brother and sister. My dad was a teacher for primary kids and my mom worked in a psychiatric hospital and became a lay therapist. She was a very kind, bright, amazing woman. I was an active kid, always playing. One day I came home with a severe headache. I went to hospital and it turned out I had a brain abscess and went into a coma, I almost died. I was in the hospital a couple of months. Part of the abscess made the bone in my left upper frontal area go rotten and so they had to take out the bone. For some years, I wore a helmet while we waited for the bones to grow back and then, when I was 13, the neurosurgeon decided to put in a plastic plate. I was endeared to the surgeon, I wanted to be like him.

DUAL PURPOSE I’ve had these two threads running through my life – philosophy and medicine. When I was very young, these questions – Who am I? What am I doing here? – plagued me all the time. I was in a philosophy club when I was about 14 and when I was 15, two books came to me on Zen Buddhism and I was very moved by them, one by D. T. Suzuki and the other by Alan Watts. I majored in philosophy at UC Berkeley. After that I wasn’t sure whether to pursue academic philosophy or not. I was always a rebel and a hippie and had long hair and a beard, so when I decided to apply to medical school, I knew it wasn’t going to be easy.

MATCH MADE IN HEAVEN I knew the woman who would become my wife when we were kids. Once a year, our families would come together to celebrate a holiday. We played a little together, but not much. When I was a student, my mom told me she was up in Berkeley. She said, “She’s pretty hip, she’s into the anti-war movement.” I think my mom was trying to set us up; she liked her and the family. For our first date we were supposed to see Ten Days that Shook the World, but it wasn’t playing so we ended up seeing Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew. Berkeley was cool and explosive, the anti-war movement was going on and we used to sometimes go to Santa Cruz on the weekend just to get a little peace and quiet. We got married three days before I started medical school. We had a three-day honeymoon – it was simply divine, nothing is ever long enough – and then Judy was in law school. We didn’t really see each other for three years because we were so busy. It’s three years for law school, four for medical school.

LOSING MYSELF I started private practice in California and a few months later Judy was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Doctors say you don’t treat your own family. I think that’s wise; I wasn’t being her doctor, I was being her nurse, giving injections and medication so we could spend a lot more time at home. We got incredibly close in that time; sometimes it felt like we were literally one person. We knew we didn’t have a lot of time … the cancer worked its way up the linings of the abdomen into the chest, the heart. She couldn’t breathe, she couldn’t talk, but she was lucid and wrote notes to people. And then she went into a coma and passed away and my life fell apart. We had been 11 years married, 14 year together. The days I could often spend with friends, occupy myself a bit, but the hardest time for me was getting into bed alone. For two or three years I was quite reckless. I nearly died kayaking in the Quinault National Forest … and there were other times – scuba diving, mountain climbing – when I don’t remember being actively suicidal, but I didn’t care.

ASIA CALLING In 1984, six months after Judy died, I went to India, Sri Lanka and Nepal for eight months. I was trying to come to terms with everything. I came back and, for about a year, tried to continue my practice, but it was hard to be in the same places and social situations so I got a job at the University of Washington, as a professor in family medicine. I was practising Buddhism and wanted to go deeper. In 1989, I took a six-month leave of absence and I went to India with one of my teachers, a yogi. I worked at the Tibetan Medical Institute, in Dharamsala, where they train their doctors, have a pharmacy and make the herbal medicines, and a clinic where they see patients.

SINS AND NEEDLES A year after I moved to India, I became the Dalai Lama’s doctor. He was planning to go to an environmental conference in Rio de Janeiro and the office got word there was an epidemic of cholera. He called me in and asked whether he should go. I said if he was careful about the food and water and had the vaccine, I thought it was OK, if it was important. I was really nervous when I gave him the injection because I thought I was violating the body of a Buddha by putting a needle in his arm. Afterwards, he took me into the next room, where he was doing a retreat. On the table was the mandala for his retreat and he took me by the hand and slowly walked around the table. There were some glass shelves and he pointed out the small statues that came out of Tibet, some where 1,000 or more years old, and he told me the history of them as he was taking me slowly around the mandala. Then he took two semi-precious stones from the mandala and gave them to me – a small crystal and a turquoise stone, which I wear around my neck all the time.

NO ORDINARY ORDINATION Years later, I did a retreat in southern France. We shaved our heads – men and women – and wore monk/nun clothing and took some of the basic vows. When I returned to Dharamsala, I went to the Dalai Lama and asked him to ordain me. He gave me some things to do and a year later, I reported back and he laughed a big laugh and said, “Yes, we’ll ordain you.” Normally he ordains a big group, 100 or more, but in my case it was just me. He gave me the novice vows and then I was offered breakfast. Normally you wait a few years before you get the full vows, but as I was leaving, his ritual master called me back. I went back in and he gave me the fully ordained vows. It took a couple of hours. There’s a group of about 12 senior monks and lamas who come together and the Dalai Lama is the main one and some of the others were my teachers. There’s one point where everyone puts their hands on each other’s and we were standing so close I could smell the tsampa on His Holiness’ breath.

KNOWLEDGE IS POWER The Dalai Lama has a small team of Western doctors and Tibetan medicine doctors and then we have places in the world where he goes to get care.When you are around him, you feel happy – not excited, but a deep, stable joy. Your practice, your meditation is better. You just feel this deep sense of total wellness. He’s very calm, very active, very alert. Sometimes it looks like he’s tough; it’s all love and compassion inside. He’s got an incredible sense of humour, he just cracks jokes, he laughs from the belly. His Mind and Life Institute has been meeting great scientists for 30 yearsin the field of cosmology, quantum physics, neuroscience and psychology; for 30 years they have been having dialogue, sometimes every year, and it’s not uncommon for a scientist’s jaw to drop and him to say, “How did you know that?” He just puts things together like a master chess player knowing seven moves ahead.

BED FELLOWS I have a room on the compound in Dharamsala. It’s an old set of buildings, built probably in the 1960s by the Indian government. A handful of us sleep there and there are offices. I was faculty for many years at the Mind and Life Institute, now I’m considered a fellow. I don’t get any salary from them, I’m more of a consultant and adviser. I’ve been working 27 years as a charitable doctor. I get zero salary. For many years, living in India was very cheap. I teach in Japan, Hong Kong, US and Russia and Mongolia – 95 per cent of the places I teach they pay for my expenses, an economy flight, simple but clean hotel and food. I teach medicine, meditation and healthy self-confidence, how to train yourself to not put anybody down.

I pinch myself all the time. it’s a privilege and an honour to serve his Holiness the Dalai Lama.

Barry Kerzin is a visiting professor at the University of Hong Kong

Original Link: SCMP